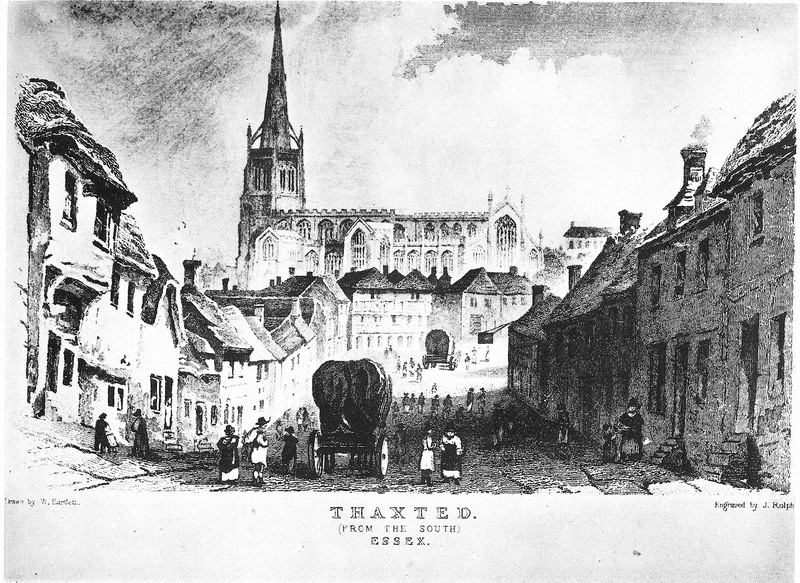

The title is taken from a mysterious inscription on one of the bells in the tower of Thaxted Church. The following was written after visiting the church, and pondering on the lack of anything other than an eight page pamphlet about the church's most famous musician who wrote 'The Planets Suite' whilst staying at Thaxted before and during the First World War. The church, that inspired one of the most popular pieces of classical music ever written, is one of the wonders of East Anglia and must be high on the list of sites to visit for anyone visiting the region.

..Whereas, of course, everything in this world-writing a letter for instance-is just one big miracle. Or rather, the universe itself is one'Gustav Holst, in a letter to Clifford Bax

The Heavenly Spheres make music for us, The Holy Twelve dance with us, All things join in the dance!, Ye who dance not, know not what we are knowing.Gustav Holst's free translation of the Acts of John in the Apocrypha

If ever I was to search for a miracle, I wouldn't have to look much further than Thaxted. Two connected miracles, in fact. On one hand there is the stupendous architecture of Thaxted Church, much of which was created at a time of misery, plague, war, and economic collapse, and on the other hand there is the Planets Suite, created in the darkest hours of the First World war. Both are artistic achievements far greater than the sum of their parts. "It is Supra-human", wrote Vaughan Williams of Holst's music, "it glows with that white radiancy in which burning heat and freezing cold become the same thing".

The man responsible for the second miracle was 'never quite the same person again' after coming upon the first, the spire of Thaxted Church towering over the flat landscape in the far distance, whilst on a walking tour. He resolved, thereafter, to live within sight of it. Essex therefore can claim one of the best of the British 20th Century composers, Gustav Holst even though he was born in Cheltenham and lived most of his life as a Londoner; for it was in a cottage near Thaxted that his most famous work, the 'Planets Suite', was written. It was originally called 'Seven Pieces for Large Orchestra' and only assumed its astrological title three years later. In fact, it took much of its inspiration from the town and its landscape. Holst's stay at Thaxted was a time of heightened inspiration for him, during which time he produced his most enduring music. Although he had a house in or around Thaxted from 1914 onwards, it was the early years during the First World War that were so important for British music, and it is certain that it was the North-Essex landscape that inspired the music by which he is best remembered.

Gustavus Theodore von Holst was of Latvian-Russian descent but he was deeply influenced by England's countryside and folksong. Until the First World War, he was named Gustav Von Holst, the 'Von' being added by his father Adolph, who was a piano teacher in Cheltenham. It was difficult to be a British musician in Victorian times where Germanic music was consistently fashionable, so Gustav's father made the name sound more Germanic for the sake of his music-tutoring business.

Holst's mother was English, and he was bought up in a house that resonated with music. He studied at the Royal College of Music in London. He settled down to a life as a church organist around Cheltenham until neuritis forced him to abandon performing on keyboard instruments. For some years he made his living as a trombone player, but eventually gravitated towards teaching, becoming master at St. Paul's Girls' School in 1905 and director of music at Morley College in 1907, posts he successfully retained until the end of his life. The teaching work gave him the drive and the stimulus to compose. He also became an avid collector of Folk Song, spurred on by his friend Ralph Vaughan Williams.

Holst's association with Thaxted started when he had already gained a small reputation as a composer, but he was unknown to the general public. His attempts at reaching the first leage of composers had failed. Holst, so the story goes, came upon Thaxted almost accidentally on a five-day walking tour of North Essex. In the winter of 1913, the short-sighted, shy, frail, middle-aged man alighted from Colchester station and had wandered around the beautiful villages of North Essex until he saw the immense spire of the Church of St John the Baptist over the fields. He was completely intoxicated by Thaxted's architecture, and the beautiful town square. He stayed at the 'Enterprise' inn in Town Street. Whilst wandering around the church, awestruck at the scale of the architecture, he met, and immediately liked, the eccentric vicar Conrad Le Dispenser Noel. Noel had become Vicar in 1910 and was to stay until his death in 1942. He had strong communist beliefs that the townspeople viewed with amusement and pride. Holst asked Noel to let him know if a house turned up in the area.

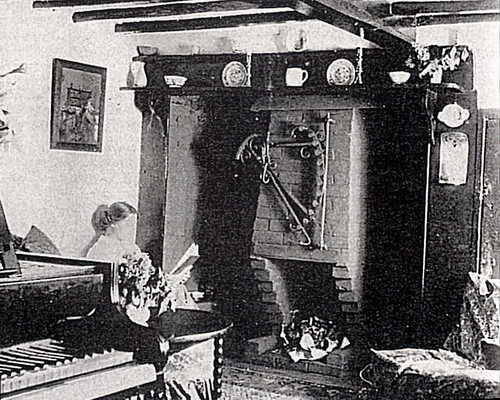

After a few months, Conrad Noel wrote to Holst about a thatched cottage a mile from Thaxted, at Monk Street, previously occupied by the writer S.L. Bensusan, which was to let. It was a charming place with open fires and a magnificent view of the church spire in the distance. Holst decided to rent it and used it as a 'weekend and holiday cottage'.

'It stood high above the surrounding cornfields and meadows and willow trees, with a view of the church spire in the distance. It was so quiet that we could hear the bees in the dark red clover beyond the garden hedge. We could watch the meadow grass being scythed, and in the cornfields we saw the farmer sowing the seed by hand, scattering it in the breeze as he strode up and down. The only traffic along what is now the main road was the carrier's cart which stopped every few hundred yards to pick up parcels and passengers on Wednesday afternoons: on the other days, people walked.'

'He liked the Essex fields, and the lanes that had to wind their war round them and the thatched cottages that looked as if they'd grown there. The valley was planted with young willow trees and a high wind would turn them to silver. And in the distance, the spire of Thaxted church stood up against the sky' (Imogen Holst 1938)

He procured a grand piano with a very light action that suited his neuritis, and it was there that he composed 'Mars the God of War', at a time that the political tensions of Europe were about to make war inevitable. It was a striking piece of music, quite unlike anything he had previously written, and in a style he never repeated.

It may have started out as homage to Stravinsky, or possibly as an ode of gratitude to an unusual piano that allowed him to translate his musical ideas so directly. Holst had been talking about creating a major orchestral work with a large orchestra. It was certainly a heady time of inspiration and the rest of the suite followed 'Mars, the God of War' rapidly. It was finished, except for 'Mercury', by 1915. The music fits quite uncannily into the stunning architecture of Thaxted church and the mediaeval core of the town and it is amusing to fit the music to the places, views, and weather. This was not the first time he'd portrayed a place in music. He'd already done so with the Beni Mora Suite, which he wrote after visiting Algeria. He returned to the idea when he wrote his 'Hammersmith' Prelude and Scherzo for orchestra (opus 52), and most famously with his chilling 'Edgon Heath'.

When he started on what subsequently became the 'Planets Suite', he had just heard Schoenberg's Five Pieces for Orchestra. Holst had also managed to hear Diaghilev presenting Firebird in 1912 and the following year Petroushka and the Rite of Spring. He was very impressed with Stravinsky's orchestration and rhythmic vigour. Undoubtedly, there is also a strong Debussy influence there as well, Neptune sounding like the final movement, Sirens, from Debussy's Nocturnes. In a sense, he is portraying in each piece, how a contemporary composer would react to the breathtaking beauty of Thaxted Church in its setting. The clue lies in the Hymn called 'Thaxted', taken from 'The Planets'. Holst was admitting that at least some of the music was about Thaxted. Each part is written in a style that is different to Holst's' own; It is an enigma, where he writes each section in the style of a different composer. Sometimes it is the bustle of the market, followed by a walk up the steep hill to the church, sometimes the fantastic experience of being up the spire on a still day, or the fields at harvest-time. The fun is in guessing the composer he was mimicking at any point. It was a party trick that he never wished to repeat and which he never admitted to. What intrigued Holst about the planets was their astrological significance, the effects on the lives of people and the naming of the planets in the various sections of the work probably have more to do with the star-signs of the composers whose work he was mimicking. 'He found that horoscopes threw an astonishing light on the strengths and weaknesses of some of his friends'

(Imogen Holst 1938)

For Holst, a city-dweller, the stay in a cottage in the country was all novelty and excitement

It was the first time he had known what it felt like to be living in the depths of the country, where the everyday things that he had always taken for granted became suddenly transformed into matters of vital importance. Water had to be pumped, and when the rain-water butts were empty the sky would be anxiously scanned for clouds of the right shape. And when the rain fell, day after day, it would prove a calamity for having interfered with they hay-making or the harvest...

Just as he was finishing 'Mars', the inevitable happened, and Europe was plunged into war. Holst's constitution was always frail, and he had no hope of being able to get into the Services, or even do useful war work, so he carried on teaching and composing. At Thaxted the townsfolk were initially wary of 'Von Holst', to the extent that the village policeman felt obliged to follow him as he went on long walks around the surrounding countryside seeking inspiration for the Planets suite. This was at a time when anti-German feeling was running high, for there were some incidents where the windows of shopkeepers suspected to be of German origin or sympathy were smashed, German grocers were suspected of poisoning food, and German Barbers of cutting throats. However, the misunderstanding was soon cleared up, the police filed a report 'many rumours are current about this man but nothing can be traced against him'. Holst was soon helping with the music at the church, being affectionately referred-to by the choir as 'our Mr Von'.

Holst helped coach the choir and introduced them to E.H. Fellowes's edition of English Madrigals, which contained the music of Thomas Weelkes.

During 1916 a growing friendship with Rev Conrad Noel, resulted in the establishment of Whitsun music festival in Thaxted church.

Holst's teaching work in London involved being the music master at St Paul's Girls School, and running Adult Education classes at Morley College. The previous year Holst had invited a few pupils of Morley College to come and sing at Thaxted, now pupils from both Morley and St. Paul's were invited to visit for the Whitsun weekend of 10-12 June. A mixture of services, concerts and garden parties ensured that the event was a great success while the music performed included Purcell, Lassus, Vittoria, and Palestrina together with the Bach mass in A. There were four days of perpetual singing and playing, either properly arranged in church, or impromptu in various houses, or in the countryside. There were fifteen Morleyites, ten girls from St Pauls, ten outsiders and ten Thaxted singers. The latter were mostly working in a local factory and had practiced their Bach Chorals every day for months at work.

'…at intervals, bars of sunlight struck down through the great windows and lit up the pillars and hangings in golden patches; Here and there on the great stone floor stood great earthenware jars filled with larkspur, peonies and beech boughs, and high up amongst the vaulting, swallows darted in and out…'

One morning Holst went to the church only to discover one of his Morley Pupils, Christine Ratcliffe, in the shadows playing her violin and softly improvising a wordless song. From this came one of Holst's most beautiful and simple works 'The Four Songs for voice and violin' which used texts from Mary Segar's 'A Medieval Anthology'. Originally, Holst hoped that Christine Ratcliffe would perform the work herself but she could not articulate the words whilst playing the violin, and it has since always been performed by two people, a singer and a violinist.

There was a second Whitsun festival in 1917. By this time, Holst was living at the Manse in the town square (then called 'The Steps'). This year the weather was kinder and again, folk dancing, folk songs, madrigals and spontaneous music making was the order of the day. They even sang Byrd's Three-part Mass' from the church tower in their exuberance.

Noel was fascinated by the inscription of one of the bells 'I ring for the General Dance', and had discovered the words of a mediaeval carol 'This have I done for my true love'. He pinned this up on the church door.

Someone complained to the bishop about Noels' use of secular lyrics in church and the bishop reproached Noel, who was able to reply that the carol had been sung since mediaeval times. Holst set the words to new music, and the result was one of Holst best-loved sacred works, second-only to 'In the bleak mid-winter'.

At this time, the 'Seven Pieces For Large Orchestra' was still being orchestrated. It had originally been scored for two pianos by two of Holst's colleagues, Vally Lasker and Nora Day. Holst's neuritis was, at times, so bad that he could scarcely hold a pencil, so the three of them worked as a team on the huge effort of scoring the work for orchestra. The original score for the 'two pianos' version still exists with the names of the planets added in later in pencil. It was in the course of this monumental work, at some time in 1916, that Holst was starting preparatory work on what later became 'The Hymn to Jesus' and heard from conrad Noel about the lines from The Acts of John in the Apocrypha. This had never been translated into English so Holst set about the task himself. In the passage as he translated it, Jesus and his disciples met on the night before the crucifixion.

'And he gathered us all together and said: 'Before I am delivered up unto them, let us sing a hymn to the Father'. He bade us make, as it were, a ring, holding one another's hands and himself standing in the midst, and said:

The Heavenly Spheres make music for us;

The Holy Twelve dance with us;

All things join in the dance!

Ye who dance not, know not what we are knowing.

...

Give ye heed unto my dancing:

In me who speak, behold yourselves;

And beholding what I do, keep silence on my mysteries.

Divine ye in dancing what I shall do;

For yours is the Passion of man what I go to endure.

Ye could not know at all what things ye endure,

Had not the Father sent me to you as a Word.

Beholding what I suffer, ye know me as the Sufferer.

And when ye had beheld it, ye were not unmoved;

But rather were ye whirled along, ye were kindled to be wise.

Had ye known how to suffer, ye would know how to suffer no more.

...

Know in me the word of wisdom!

And with me cry again:

Glory to thee, Father!

Glory to thee, Word!

Glory to thee, Holy Spirit!

Amen.

Holst suddenly had the theme, the name, and the link between Thaxted, the dance, and the music. 'The Heavenly Spheres make music for us' in the Planets Suite, and the bell in the tower 'rings for the General Dance'. It was the dance of the planets, each in their own astrological character

On September 29th 1918, the 'Seven Pieces for Large Orchestra', by now unofficially called 'The Planets', had its first performance. Imogen Holst remembered the occasion...

The orchestra rehearsed for just under two hours and then played the work straight through. The two or three hundred friends and fellow musicians who had come to listen in the half-dark auditorium realized that this was no ordinary occasion: the music was unlike anything they had ever heard before. They found the clamor of Mars almost unbearable after having lived through four years of a war that was still going on. The cool to-and-fro of the chords in Venus had a balanced tranquility that had not yet become a familiar device. The scurry of Mercury was breathlessly exciting; I can remember, during the tuning up in the rehearsal, seeing and hearing all those violinists frantically trying to decide on the right fingering for their rapid high quavers. Jupiter was thoroughly happy, without any of the false associations that were afterwards to link the big tune to the words of a patriotic hymn. In Saturn, the middle-aged listeners in the audience felt they were growing older and older as the slow relentless tread came nearer ... The magical moment in Uranus was when all the noise was suddenly blotted out, leaving a quietness that seemed as remote as the planet in the sky. It was the end of Neptune that was more memorable than anything else at the first performance. Hearing the voices of the hidden choir growing fainter and fainter, it was impossible to know where the sound ended and the silence began.

The concert was not the success that was hoped for. It was two years later that the first full performance made Holst famous overnight, to his deep displeasure.

Sadly, the Whitsuntide festival ceased after 1918. Holst was abroad for much of the year working for the YMCA, undertaking the role of Musical Organiser for troops of the Army of the Black Sea, working in Salonika and Constantinople. When the Whitsuntide concerts were revived, St Pauls School, Holst's employer, insisted that the venue should be Dulwich. Conrad Noel's communist rants from the pulpit had become too much for the parents of the St Pauls pupils, and so Thaxted lost what could have become a great annual event. After the end of the war, the success of 'The Planets' led to a busy part of his life teaching and lecturing.

After a head-injury in February 1923, he began to show the signs of overwork and, on strict medical advice, retired back to his beloved Thaxted for a long holiday, spending only one day a week in London.

Holst was never one to be lazy, and he found it impossible to relax. For a while, his breakdown got worse; although it was a year since his head injury, he began to have violent pains in the back of his head; even when the pains ceased he could not bear anything touching his head - not even a hat or a pillow. Noise was a torture to him: people talking, applause, traffic. He had nightmares about making mistakes or about his creativity drying up. His doctor became alarmed and implored him to rest, advising him to give up all work for the rest of that year. Slowly he improved but he was never able to resume any regular teaching except for a very little at St Pauls where he continued to teach to the end of his life.

He lived for nearly a year in 'The Steps' (now 'The Manse') in the middle of Thaxted - alone most of the time except for an ex-army batman who became Holst's cook, valet and guardian. He worked on his Choral Symphony and a new opera 'At The Boars Head' based on the Falstaff scenes from Henry IV. By the end of the year, he was making progress toward recovery.

In 1925, the family moved to a large Elizabethan house at 'Brook End' some miles from Thaxted' &

...full of old oak beams that had never been stained but were a soft grey. There were large open fires, and the glow from the logs was reflected in the shining pewter and the rich colour of the hangings…

but Holst had a renewed energy and only appeared at occasional weekends, filling his week with teaching, lecturing and composition. He was restless and seemed to have no desire for a fixed home. In London he was happy enough going for solitary walks. It was a time when some of Holst's finest works were produced, including his wonderful settings to Seven poems of Robert Bridges.*op 44.) 'I did the first of the Bridges poems the moment I caught sight of the words, since when I've been wondering what they mean!

By the early thirties The Holst family were living in a smaller cottage at Great Easton.

Holst died in 1934. Despite his illness, he wrote the work which singles him out as one of the most creative of the twentieth century composers, the wonderful 'Six Canons for Unaccompanied voices'. It was a complex work, sometimes in three simultaneous keys, but with a great intensity that marks it out for greatness. In particular, his setting of Peter Abelard's glorious hymn 'How Mighty are the Sabbaths, how mighty and how deep'

is an astonishing setting, full of an emotional involvement that his critics often denied that he possessed. It is hard to listen to 'A Love Song' without a lump in the throat:

Thy hair hath entangled

my very heart's fibre

the flame is upleaping

and sinking my soul

Love the deceiver

love the all conquering,

come to mine aid'

Holst's frail health had given way when he was creating his greatest music.

The truth of Holst's stay at Thaxted is probably more complex that the story given by his daughter Imogen in her famous biography. Conrad Le Dispenser Noel owed his appointment to Thaxted Church to patron of the living, the eccentric Countess of Warwick, the owner of nearby Easton Lodge, one of the grandest of the Essex estates. In Thaxted church, Noel became famous for his Plainsong, incense, flower-processions, folk-dancing and radical politics. Noel set up a "Chapel of John Ball, priest and martyr, 1381," behind a little panelled door. Noel flew a red flag over his church during the General Strike, and on every May Day. He also tied the knot between folk music and socialism. He was a man of immense charm and energy and he was loved by everyone who knew him, but his politics were, at the time, somewhat bewildering.

Noel's patron, Daisy, inherited the Easton Lodge estate. She, had once been singled out as a suitable bride for Queen Victoria's youngest son Leopold, but instead married his equerry, Lord Brooke. She remained part of the royal circle, and entertained royalty in lavish style at her house.

Later, as the Countess of Warwick, she wholeheartedly embraced Fabian Socialism and fought with vigour for better standards of health and education. She advocated a great number of the ideas that later became enshrined in the welfare state, but her zeal owed much to the arts and crafts movement, and the ideas of G Bernard Shaw.

Daisy seemed to have the ambition to create a hothouse of socialist thought in the huge estate around Easton Lodge. Amongst her many visitors was Ramsay MacDonald, who adored the aristocracy. But so did the firebrand socialist and trades-unionist Manny Shinwell. Chaplin came, though only to play charades. She became an early environmentalist: the house swarmed with animals, including a collection of monkeys.

Daisy Warwick's family house, Easton Lodge, was the model both for Shaw's Heartbreak House and for Claverings, the mansion in Wells' war novel, Mr Britling Sees It Through. Wells and his wife lived in a house on the estate. Shaw often visited. So did everyone who was anyone in early English socialism.

Around Thaxted and Dunmow, she aimed to establish a community of left-wing artists. H.G. Wells, Gustav Holst , S.L. Bensusan, H. de Vere Stacpoole and J. Robertson Scott, founder-editor of "The Countryman" magazine, and Philip Guedalla became her tenants and the living of Thaxted was given to a succession of socialist priests, much to the bemusement of the parish. Amongst her neighbours and friends were the newspaper editors R.D. Blumenfeld, (The Daily and Sunday Express), H.A. Gwynne (The Morning Post), and Kingsley Martin (The New Statesman).

Gustav Holst, a socialist composer, was essential to her vision of a community of like-minded artists, and so he came to be one of her tenants. It is not known whether Gustav Holst was introduced to her via Conrad Noel or whether the apparent impulsiveness of Holst's move to Thaxted concealed a more deliberate and long-term plan. Whatever lay behind the move, Gustav Holst delighted his new patron by writing Christian Socialist music for "People's Processions" at Thaxted, and his music always held true to Fabian principles.

Only the shreds and relics of Easton Lodge are left. The Countess's lifestyle and generosity to the Socialist cause led to financial difficulties with the estate and she constantly had to sell off land. The Countess had made the house the scene of innumerable Labour gatherings. She offered to give it to the TUC, but it backed off, scared by the cost of maintenance.

The second world war spelled the end of the estate. After her death, the house was requisitioned for the American air force, and most of the remaining land laid out as a base for the 386th Bomb Group and its B-26s. After the war, most of the house was pulled down.

Now, Thaxted is in reach of the motorway, and threatened by the expansion of Stanstead airport. The church is still stupendous, and looks quite similar to the way it did when it changed Holst's life. The quiet has gone, since jets scream low overhead at regular intervals but it is not hard to block out the noise and imagine that magical Whitsun Festival of 1916 when a small number of amateur musicians inspired Holst in ways that were to change British music for ever.

Of the Planets Suite itself, what can be said? The interpretation of the music is so personal that one blushes to come up with an interpretation. However, Holst, in his Hammersmith Suite was so clear in his interpretation of a scene that it is like incidental 'film' music. It is the same with the 'Planets', particularly with 'Jupiter'