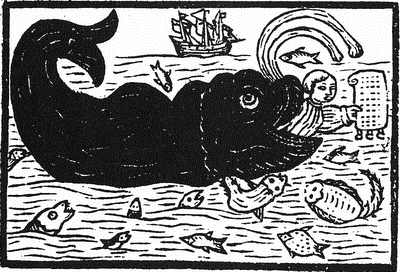

Mary Whale, about to serve up some 'Watkins Ale'

One would normally expect a poet to be delighted by hearing the news that a poem he had written had become such a hit that the whole town was reciting it. However, when an impoverished teacher called Chitham heard that his ballad was being recited in every Beerhouse in Chelmsford, his worst fears were confirmed. He had been tricked into writing a hit ballad by a barber-surgeon who was hoping to exact a vengeance on s young lady.

The twilight years of Elizabeth's reign saw the roguish barber, Hugh Barker, achieve some notoriety in Chelmsford as 'a very troublesome and dangerous fellow and a raiser of great seditions among his neighbours'. Having secured the services of a Boreham Schoolmaster called Thomas Chitham to compose a slanderous ballad, Barker unwittingly set in train a sequence of events that led to public outrage, attempted bribery and an extraordinary case of libel. Thankfully the sorry tale has been preserved for posterity in the report of the Chelmsford Hundred Jury.

In October 1601 Chitham visited Barker's house because he was paying a visit to a sick friend and was in need of a haircut. Seeing that he was a man of considerable education, Barker came forward with a rather unusual request, 'It is nothing but to have you pen a few verses for me upon a petty jest which I shall tell you'. Perhaps sensing trouble in the offing, Chitham was reluctant to perform this favour. However, on his third visit to the barber curiosity got the better of him and he agreed to write the poem. Barker then told Chitham of the scandalous dealings between Clement Pope, a Glover of Chelmsford, and the unfortunately named Mary Whale. Mary was the bride of John Whale the tailor, who was Pope's brother in law. This tale was clearly saucy stuff, according to Chitham's later testimony 'with such lascivious terms did he intermingle his discourse as I am ashamed to think on, much less can I with modesty dare -for fear to offend the virtuous and chaste minded- to presume to set them down'.

Chitham claimed that he had been outraged by the tale and declared 'that if it was his intention to publish it to the disgrace of any, he would not set his hand to paper for a thousand pounds'. In reply Barker promised that 'it should not come to anyone's sight save his own' and that his only purpose for the ditty would be 'to sing to his citron and to laugh at when he was melancholy'. The barber then went to the back of his shop to emerge later with pen and ink and 'in a most villainous sort plotted how he would have it done'. It is tempting to adopt a degree of cynicism when reading Chitham's self-righteous testimony. He certainly had few reservations in composing the 'four staves of verses' and between the lines of the elegy one can detect a certain relish in producing such scurrilous material. It was Chitham's intention, so he said, to 'write not so beastly, but cover the filthiness of fact under as cleanly terms as possible'. If this was indeed his aim he failed miserably, for underneath the marks of Classical imagery the details of the scandal were all too discernable.

Sometime a mighty huge Leviathan arrived

In brave Albion's eastern parts

It was a mighty fish and now and then he went abroad

And glanced forth his darts

Men, women, boys and girls he held as one

And all men know a Whale is big of bone

What though his entrails like the Caron's flood do

Swallow up the giddy headed crew

We often see this might Cetus blood

With needles pressed and I'll approve it true.

But what he cannot do his female make

Will undertake it to finish for his sake

Admit the Pope did practice Glover's art

And come to Chelmsford bragging of his skill

In Venus may games in spite of his heart

She'll meet him at the point and fit his will

And if her husband takes him at the fray

Up goes his hose and fast he runs away

She knows her wards and in the fencers game

Hath proper knowledge, let her use it well

Lest soaring high she lose inferior fame

And so her not with Cerberus do dwell

Well, Whale, look thy wife, I am thy friend

I wish thou what thou hast and So farewell

To the whole generation of vipers health

Having written these lines, Chitham handed them to Barker who instantly displayed his lack of trustworthiness by breaking his promise and eagerly reading the poem to his wife. This rang alarm bells in Chitham's mind and he asked for the lines back. His request was refused and he decided to return home. Later on he was to wish that he had been more forceful.

We can only begin to imagine the growing sense of horror and realisation that Chitham must have felt when he stopped off at the New Inn in Chelmsford and was informed by the townsmen of 'certain libels' that were spreading through the town. A certain John Barker was rumoured to be the author of the slander and as Chitham was noted for having been familiar with him, he attracted a certain degree of suspicion from the assembled company. Perhaps sensing this, Chitham protested his innocence and agreed to convene with John Whale the next Friday. Having met with the irate Tailor he decided to come clean and admitted he had written some of the verses. However, Whale then produced another ballad, one which Chitham describes as of 'certain lascivious, villainous and beastly rhymes which I protest I never saw before Goodman Whale showed them me'. This seems an unfair criticism as the poem he now read was of comparable obscenity to the one he had composed for Barker. It read

You that be wise listen a while

And mark the tenor of my style,

And weigh the cause in each degree,

The matter is manifest to be.

As for all fools, let them be still

For wedded they are unto a will

To slander eke both foe and friend,

But gallows tall will be their end.

Some say a battle late there was

Between a lad and a Bonny lass

John Whales wife that lofty lad

Old William Shether was her dad

The other was a Barber born

Which Edwick's minikin held in scorn

Called Mary White that bonny lass

But her husband is a very ass

For if that he were very wise

He would shore open both his eyes

And see the doings of his wife

And learn her to amend her life

For if she do not tell him true,

Both head and horns shall be his due

The barber as I understand

Did take her co in his hand

But if Clim Poope were now alive

He would not wish himself to thrive

Till he had cuckold his brother Whale

But tut, this news is very stale

For Thomas Phillips swears the same

The same that he did occupy his dame

And got of her a goodly boy

Called Robyn, all her only joy

Some secret thing was in the wind

I am persuaded in my mind

Which made the battle to begin

John Whale by this did six pence win

Money enough considering all

The barbers beating and his great fall

Among the nettles that did him sting

Because a token he did bring

Which was devised by her husband John

No cogging knave, but an honest man

If Edwick nubs not Mary Whale

And gives her store of Watkins ale

Hang me at the next tree that grows

And let me have as many blows

As Barker had at that same fray

I know not but as some do say

Whether he had any yea or no

But by hearsay, but let it go

But if he had it was no hurt

The discredit longs to such a flirt

As Mary Whale that Flanders mare

That care no who doth touch her gear

I understand there is a song

Made by a dishonest throng

Of Mary Whale and Hugh Barker

And Mistress Almond loves John Parker

And will do so still and so she says

If Beelzebub lighten forth her days

But whosoever made that song

Let him repair to me John Long

He shall have me at Goodman Fuller

A dyeing of him in divers colour

Which shortly shall a drying hang

And nip you all with a lurry come twang

Vale from my chamber in Duckes Street Lane

If this will not give you your bane

I have another ready made

Which will unfold your knavish trade

Commend me also to Mary Whale

And if she needs of Watkins Ale

Clim Poope is dead but Phillipps lives

With Watkins Ale to such mates gives,

Yours if you use him John Long the carrier

Dwelling next door to Evens the farrier.

Perhaps racked by guilt, Chitham agreed to report the matter to Sir Thomas Mildmay, the local justice of the peace in order to pursue an indictment against Barker at the Epiphany Quarter. This trial was postponed until the next sessions, and in the interim Barker made numerous attempts to bribe the Schoolmaster and coerce him into ending legal proceedings.

On the first occasion, Chitham found himself at the house of the husband of one of Barker's sisters whilst performing an errand. He was delayed there by a musician on the false pretext that his help was needed to pen a love song. The true purpose was to buy time, and presently Barker arrived to tell Chitham that if he pursued the suit he would be 'utterly undone'. Having threatened him, he then entreated him to stay in Chelmsford at his expense 'because it shall not be apparent that I wage you to this, my wife shall from time to time send you money'. Barker later provided further incentive by sending his son to the house to cut Chitham's hair free of charge. The next day he informed him that 'he wished me to forsake my great charge of children and my poor wife and shift for myself, alleging that I was fit to live anywhere and wherever I went he would help me'. On the surface this charm offensive appeared to be working because the next day Chitham agreed to write a letter to Barker in which he would 'acknowledge some injury I had offered him'. Chitham clearly felt he had no choice but to comply, being of poor means and under relentless pressure from Barker.

Having gained this concession, Barker sensed he had the upper hand and asked more and more favours of Chitham to further extricate himself from prosecution. Chitham met with Barker at the barbers house and was taken to an upper chamber 'hung around with painted cloth whereupon was described the history of Hammon and his sons'. He was persuaded to write another letter, and Barker then sent for three of his friends in order to tell them that Chitham has written to him to desire to speak with him. This was -as Chitham was later to testify- 'giving me terms at his pleasure (myself being in the house within the hearing of my own doom'.

Barker then met Chitham again the next day and caused him to write a letter to three justices of the peace and a petition to Sir Thomas Mildmay in order to 'colour Barker's cause'. The barber had pushed things too far and by this time Chitham was clearly fed up with the whole affair. He had also thought of a way to escape from Barker's clutches, by asking for the help of his wealthy uncle Mr Justinian Carey. Chitham left Chelmsford to stay with his relative, resolving to return before the Easter sessions to 'bewray(divulge) the whole drift of Barker's deceitful practices'.

Upon returning, Barker's wife made a final effort to persuade him not to testify by offering him her husbands doublet and telling him 'of divers practices which Goodman Whale had practiced against me in my absence, which afterwards I proved to be mere fictions, only to make me fly the country and forsake my wife and children'. Chitham 'soothed' her, giving her the impression of compliance but having already resolved to instigate proceedings against her husband the very next day.

The Easter sessions finally came, Chitham testified and the gloves were off. At the following assizes Barker accused Chitham of perjury and charged him to be 'a rogue, a counterfeit soldier, a beggar on the highway, etc', he also procured a writ to sue Chitham, John Phillips, John Whale and his wife at one of the courts in London. By unlucky coincidence, Barker happened to bump into Chitham whilst wandering Chelmsford in the dark. The barber exclaimed 'Gods wounds!, you are Chitham' and drew a dagger on him. It was either too dark or Barker was too clumsy, for both the swings he too at the schoolmaster missed and the fortunate Chitham was able to make good his escape.

The courts were unimpressed by Barker's roguish behaviour and his scurrilous attempts to prevent the course of justice. The judgement read 'Guilty, to be imprisoned for one year and in the interim, and to be placed in the pillory in four markets, viz.: Chelmsford, Witham, Braintree and Billericay and to pay to the Queen £40. At the end of the year in prison to find security for good behaviour.'

Barker apparently did not learn his lesson. A later document of 1615 shows how a petition was made against him by the mother of a former apprentice. The lad had been bound to him for eight years to be instructed by Barker in the trade of 'barber, scrivener, tooth-drawing and bloodletting'. The barber had fallen too far into debt and two years into the lad's apprenticeship, he decided to return him to his mothers care whilst providing no money for his maintenance. In addition, he refused to release him from his indenture unless the mother gave him money for the lad's discharge. The courts decided to annul the apprenticeship and ordered Barker wife to return the boy's clothes.

Barker was later indicted for 'transgressions and contempt's' and failing to appear after the statutory three proclamations. In 1618 he was outlawed, and so his roguish career came to a suitably miserable end. It is not recorded whether Mrs Whale was in fact as promiscuous as the ballad suggested. We do know that Clement Pope generously left his buff doublet to John Whale in his will of 1598, but whether out of affection for his brother in law, or as an apology for his indisgression we shall never really know.