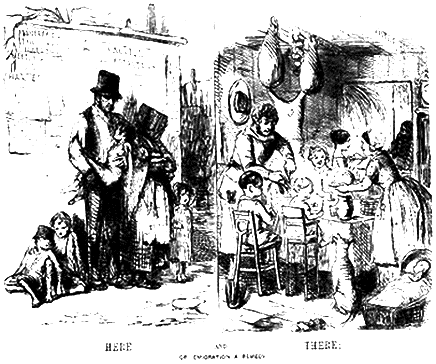

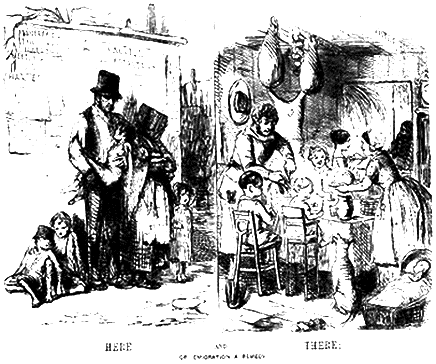

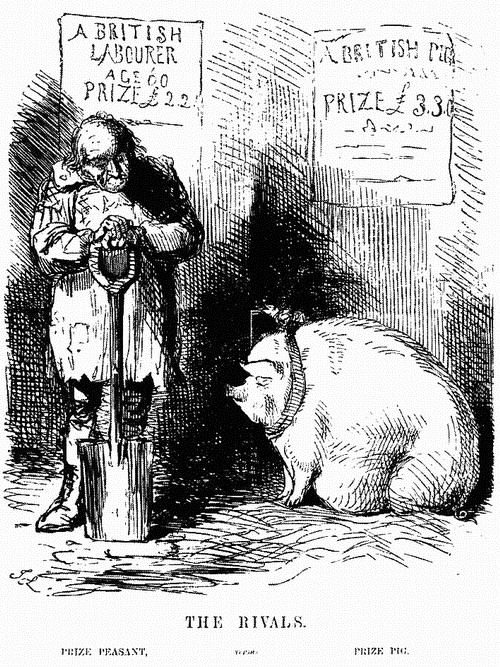

Emigration, a remedy, a Punch cartoon commenting on the Irish Famine

of the 1840s. Over the course of the 19th century,migration would

similarly become seen as the remedy to East Anglia's problems

At Wickham St Paul, in 1874, the schoolchildren sang 'The Emigrant Ship' to the schools inspector. A

poignant illustration of the way that, by then, Emigration had become part of the

culture, in a rural population that Britain no longer wanted. The steady stream

of emigrants from East Anglia to Canada, Australia, The United States and

New Zealand became a vast flood of hopeful humanity as Victoria's reign progressed, fleeing a homeland

without jobs or prospects. As in Ireland, the collapse of the

agricultural economy brought about by cheap imports was not compensated

by a rise in industry. The Industrial Revolution passed East Anglia by and the countryside

slid into a recession that was to last eighty years

The Foxearth & Distrivt Local History Society

|

Emigration in East Anglia 1800-1834 |

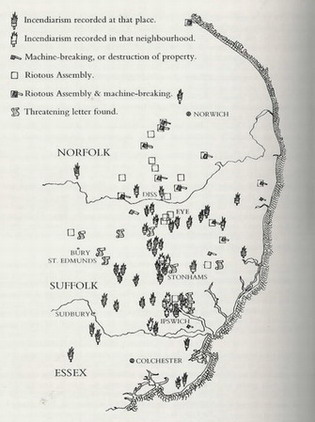

East Anglia, comprising the three eastern counties of Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk, was for centuries the crucible of agricultural advancement in Britain, but it was hard hit by the devastation of the agricultural sector after the Napoleonic wars. To make matters worse, the cottage spinning and plaiting industries collapsed around the same period. Such was the unemployment, and consequent disorder, that parish authorities were forced to explore the possibilities of assisted passages to deal with the rural unemployed. Emigration increased throughout the 1830s and became widely popularised after 1850.

The 1870's and 1880's saw extensive rural depopulation as people migrated to urban and industrial areas, with significant numbers choosing to move overseas to the USA, Canada and Australia.

English emigration is not a fashionable subject for historians. Studies of rural Britain commonly concentrate on internal migration. Those that do touch on overseas emigration focus on the 1830s and the New Poor Law debate, of which East Anglia was an important element. Most studies ignore emigration in the second half of the century completely. An analysis of mass movement in Britain suffers from the fact that the British government largely lost interest in emigration in the 1850s, before the large scale emigration of the 1880s. During the peak of emigration in the late 19th century, virtually no data was collected and the figures that do exist are inaccurate and unreliable.

'My brother is uncomfortable about the state of things in Suffolk - never a night without seeing fires near or at a distance'

(John Constable letter to John Fisher of 13th of April 1822)

The lowers orders of people are, in the altered and novel state of this country, presented only with the gloomy prospect of being, for their long tired unshaken loyalty…speedily reduced, by a restless force of absolute authority, to a wretched state of subjugation to the ruling powers'.

(Robert Small, Ipswich Journal 11th of February 1815)

During the early 1800s, emigration gradually increased in England, as it had earlier in Ireland and Scotland, as a reaction to the destruction of the traditional structures of rural society. By the 1830s emigration had become a significant drain on the population of rural England for the first time .Arthur Redford, Labour Migration In England (1800-1850), p173 (29-34) In the impoverished parishes of East Anglia it was to reach an importance most counties would not see until the mid nineteenth century. At the beginning of the 1800s, emigration was stifled by the Napoleonic Wars, which brought restrictions on overseas travel and increased the prosperity of agriculture. The demand for corn, and the large labour force required to harvest it, had fostered a healthy rural economy. However, with the end of the wars, demand eased and rural England slid into economic depression, encumbered by a destitute surplus labour force.

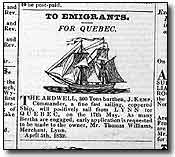

Government schemes for emigration began soon after the end of the wars in 1815 when transports returning troops from Canada were encouraged to take on passengers at low rates. An early scheme for Canadian settlement can be seen in the Bury and Norwich Free Press in 1792, which advertised 'Lands in British America…. where there is a good market for grain and other production from the earth '.Bury and Norwich Free Press, October 31st 1792 In the early 1820s the British governement made four large grants to encourage emigration which ultimately proved unpopular. Government-assisted migration still held a certain stigma because of the previous transportation of convicts and the luddites. Emigration was also despised in some circles because it was felt that the departure of the English agricultural labourer would encourage an already serious Irish influx and that, as a result, vagrancy would spread. Despite these negative assessments, some political commentators saw emigration as offering the most effective solution to Britain's domestic problems. A political pamphlet of 1828 extolled its virtues

'There is reason to hope for the greatest and most important results from connecting emigration and the repeal of the poor laws, so as to accomplish at once relief for the present and security for the future '.Hints on emigration, as the means of effecting the repeal of the poor laws / [Anon.]. p25 (30-39)

Long before emigration had become popular in the 1860s East Anglia's labourers were moving overseas to North America. From 1830 to 1833 there was a huge increase in the volume of emigration, especially from Suffolk and Norfolk which both displayed substantial local decreases in the 1831 census. The root cause of these migrations was the long and sustained depression in East Anglia's rural economy following the Napoleonic wars and the pronounced deflation that accompanied the onset of peace. East Anglia experienced widespread wage cuts and unemployment coupled with a severe downturn in the rural trade cycle. This burdened the agricultural workforce with an increased cost of living yet insufficient wages and poor relief to compensate .T. L Richardson Agricultural labourers wages and the cost of living in Essex 1790-1840: A contribution to the standard of living debate in Land Labour and Agriculture p82 (25-36) As the early nineteenth century progressed and the existing poor law was gradually reformed to relieve the overburdened ratepayer, the possibilities of assisted emigration were explored.

In East Anglia the farmers had been the victims of their own success. In Suffolk in particular, the heavy clay soils of the central belt demanded new and innovative techniques, and instilled a spirit of innovation that powered the county's agriculture way ahead of most Midland counties. Since the sixteenth century, farmers of the region had developed the Norfolk four course rotation system, the six course rotation system, the use of turnips as a root crop and a system of hollow draining. Better quality land in Suffolk was enclosed well before the days of parliamentary acts by a system of tacit agreement between the manorial lord and his tenants .Joan Thirsk, Suffolk Farming in the Nineteenth Century p21 (13-30) in Suffolk Farming in the Nineteenth Century, edited by J Thirsk and J Imray This was quicker, and far less expensive than a Government Act. As a consequence, during the high prices and grain shortages of the Napoleonic wars farmers were enabled by these developments to convert their land use to grain production in a far shorter time. When the wars ended and the depression took hold, East Anglian agriculture was left highly vulnerable to the inevitable slump in grain prices. Farmers, however, continued to plough up dairy pasture to make room for corn believing that the eastern counties dry climate could never produce good grassland and its produce could not compete with the low prices of imported Dutch and Irish dairy products. Distressed farmers, vulnerable to bad harvests, faced the dilemma that, if they reduced losses by cutting labour costs, they would aggravate the bill they were required to pay towards the parish for poor relief Suffolk Farming in the Nineteenth Century, edited by J Thirsk and J Imray p22 (10-22). The population of the region had been increasing steadily since 1800 and the prosperity of the war years had attracted settlers into previously neglected areas. This large and expanding rural population now felt the full force of mass unemployment and depression, as this letter to Lord Sidmouth illustrates.

'The state of the labouring poor is truly miserable. Such is the want of employment that stout active young men are employed by the overseers, at three or four shillings a week, merely to prevent them from starving …The labouring poor in husbandry (including disabled men from the army and navy) are not four fifths employed. The poor rates …are higher than at any period in the last forty years 'Letters from W.Sproule of Bardfield and Lewis Majende to Lord Sidmouth (27-29 May 1816) quoted in T. L Richardson p83 (4-9)

Despite a brief drop in the cost of living in 1817 and a rise in poor relief expenditure in 1816, short time working and unemployment reduced wages to levels that threatened those labourers who had large families to support. At Audley End in Essex for example, wages fell from an average of 10s 0d a week to 8s 5d by 1823 .T. L Richardson Agricultural labourers wages and the cost of living in Essex 1790-1840 In response to this, the Speenhamland allowances were widely introduced, placing a large financial burden on parish authorities but scarcely bringing wages above subsistence level. The situation was made worse by the protracted decay of the Norfolk worsted industry and the textile production based on the Suffolk Essex border. This destruction of the livelihoods of spinners and hand-loom weavers had a devastating effect in a region like East Anglia that was geared towards wheat production and therefore provided largely seasonal employment .Anne Digby, The Labour Market and the Continuity of Social policy after 1834: The Case of the Eastern Counties (Journal of Economic History 1975), p70 (4-8) Home spinning had been the traditional occupation of the women folk that supplemented the family income. Its disappearance greatly increased the problems faced by the rural poor. As a consequence the predicament of the agricultural labourer in the 1820s and 1830s was desperate, a fact demonstrated by his diet, which included little meat and much bread and potato, often, he drank nothing but water. The situation was worsened by the way in which the East Anglian labourer was estranged from his employer. From the time of the Anglo-Saxon conquest, villages in the eastern counties had had a high proportion of freeholders who made up the ruling members but were too numerous to run it in any effective way. Villages under this system grew without much hindrance, by the nineteenth century they had become known as 'open villages' forming a pool of labour for surrounding farms. In contrast to northern regions the labourer of the Eastern counties had little fellow feeling with his employer and did not share in his domestic life, he was at the mercy of casual landlords with little sense of social responsibility and employers who were too hard hit by depression to be generous to his labourers .Joan Thirsk, Suffolk Farming in the Nineteenth Century p22 (10-22) in Suffolk Farming in the Nineteenth Century, edited by J Thirsk and J Imray p31 (30-35) Encouraged by the price inflation and profits of the Napoleonic wars, the relationship between farmer and labourer had become no more than an economic one, in which men were only employed as and when they were needed The system of employing labourers on a daily or hourly basis made it easy and tempting for farmers to employ on a short time basis to cut expenses, at the same time the development of mechanisation meant that less men were required. As one contemporary noted

' The labourer is now, in general, the mere servant of the day, or of the season; and is cast off, when the task is done, to seek a precarious subsistence from other work, if he can find it; if not from the parish rates '

A Collet A Letter to Thomas Sherlock Gooch esq M.P Halesworth 1824 p2 quoted in Constable, the painter and his landscape by Michael RosenthalIn times of depression the system of the eastern counties was therefore more likely to cause frictions and animosities and so it proved.

'the evil is to come…our numbers are great and are men capable of doing upon the plan we act upon as wonders without discovery-more fires shall be witnessed'

The 'Secret Avenger', letter to Francis Seekamp

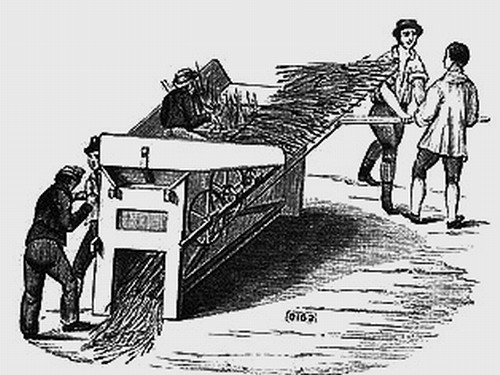

The arrival of the hated threshing machine in agricultural society provided the impetus for agrarian disturbances in 1816, 1822 and later in 1830. These outbreaks of machine breaking, riotous assemblies and Incendiarism were an ugly symptom of the destruction of traditional social structures in agrarian society. Solving the problems of East Anglia's countryside therefore became a matter of urgent attention.

"I have just returned from the place where the rioters have assembled to the amount of 200 people armed with implements of agriculture as weapons.

The Bury & Norwich Post May 28th 1816

Last night they destroyed Mr John Smith's threshing machines then this morning they visited Mr Robert Smith's farm at Byton Hall and destroyed a plough on a new construction.

On Friday last there was a crowd of nearly 200, armed with axes, saws, spades etc, when they entered the village of Gt Bardfield with the intention of destroying threshing machines, mole ploughs etc, they made their attack on the premises of Mr Philip Spicer who had the spirit and resolution to defend his property with the assistance of 20 of his neighbours who were unarmed and by the Waterloo movement got between the rioters and the barn where the machines were and they wisely retreated."

As a consequence East Anglian parish authorities saw emigration as a cheap method of disposing of their surplus workers, long before it became the official remedy. Despite the expense of emigration, there was sufficient capital available to allow the destitute to consider it as an option. Describing how the money had been raised a government report stated that 'The funds were in most cases advanced by the parish, which were either borrowed from private individuals or from country bankers to be repaid by instalments from the rates '.British Parliamentary Papers, Poor Law session 1834 Appendix A p375 (60-64)

Contrary to the beliefs of many of those who formulated the Poor Law of 1834, the cost of poor relief was not growing faster than the population, nor than the national product in the 1820's. The problem was that the cost fell unequally with impoverished parishes attaining a far higher burden than wealthier ones .M A Crowther, The Workhouse System 1834-1929, p23 (29-30) Such an antiquated and complex system put a huge burden on those of East Anglia's parishes with a large and underemployed labour workforce. The unemployment figures for the Blything and Hoxne hundreds demonstrate the expense of providing for such a large number of rural unemployed. Assisted emigration was consequently a useful method of saving money in poor relief in the short term, rather than an over elaborate method of removing paupers. The search for such an extreme solution is perhaps not surprising given the extent of the problem and the marked concerns of the farmers who had to pay the rates. John Lay who compiled the Blything and Hoxne statistics noted that 'nothing less than some legislative enactment will sett us a going again or suffer us to remain upon our farms 'The Agricultural labourers, in Suffolk Farming in the Nineteenth Century, edited by J Thirsk and J Imray p134 (40)

| Number out of Employment | 1001 |

| Wives belonging | 602 |

| Children | 2399 |

| Total | 4002 |

| Cost for the month | £938 s.9 d.4 |

| Outdoor relief for the same month and those maintained in the house | £844 s.11 d.8 |

| Total expense of poor | £1783 s.1 |

| Able bodied Men | No out of employment | Monthly Cost | |

| Baddingdon | 110 | 60 | £8 s.5 d.4 |

| Denningtone | 150 | 65 | £65 s.12 d.8 |

| Wilby | 71 | 32 | £80 |

| Laxfield | 100 | 55 | £73 |

| Stradbrooke | 110 | 70 | £97 |

| Fressingfield | 140 | 110 | £176 |

| Framlingham | 200 | 160 | £222 s.10 |

For those able to leave, North America proved a popular destination. A great demand for labour in some parts of United States offered the prospect of employment, there was also the draw of the fertile lands of the Midwest that had become open to agricultural settlement. Assisted and unassisted emigration to the North America took place in East Anglia throughout the 1830s. Several incidents were mentioned in the Bury and Norwich post which in April 1830 reported '78 men women and children passing through Bury from Diss, Palgrave and Wortham and 59 from Winfarthing and Shelfhanger in two stage wagons on their way to London to take shipping to America' in 'high spirits ' A later article reported another 50 emigrants from the same area departing to London to board a ship 'bound for Philadelphia 'Bury and Norwich Post, May 27th 1835. In such instances of assisted emigration, the parish usually provided any necessary shoes and clothing. When a further 52 people emigrated to America from Winfarthing in 1836-7, the bill of £479 14s 1¼d included £17 7s 6d for shoes, £7 7s 9d for clothing, plus £8 for clothing quoted in Joy Lody, Return of the Natives, Edp24 2002. These waves of migrants had come from the Diss Hundred, an area of high unemployment severely affected by threshing machine riots in the 1823 and during the 'Swing' disturbances when four out of its fifteen parishes broke into open riot over tithes and wages. In making the passage to the United States they were generally making the journey to the rich and extensive lands east of the Allegenies. For years, the United States had been promoted in emigration pamphlets as 'a country of hospitality which the wild Arab never violates' and where a labourer might raise himself by industry to the level of farmer were he to head for 'the countries west of the Allegheny mountains, that is Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky and Tennessee or the Illinois 'Mr. Souter ... and J. Knight 'The emigrant's best instructor, or, the most recent and important information respecting the United States of America'. An example of a Suffolk emigrant who made the journey to the American West was John Styring who was so confident of his prospects that when he emigrated to Ohio he took his 80 year old mother in law.

'Ohio is a great state for growing wheat which they raise in abundance owing to the land being rich…I am about to become a farmer bye and by, I bought a farm last November of 82 acres for 640 dollars of which I paid 150 dollars down and the balance in 5 years …old Mrs Slackforth is pretty well and had her health remarkably good since coming to America 'Bury and Norwich Post April 30th 1851.

The United States held a considerble draw to those like John Styring who wished to become small farmers. The authorites made it a rule not to press for the whole of the purchase price at the time of effecting a sale, instead requiring payment over a four year period. Farmers were also able to take advantage of pre-emption acts, offering farms at reduced charges to colonists who would live there for a certain length of timeArthur Redford, Labour Migration In England (1800-1850), p202 (1-8) . Emigrants to these territories were satisfied with their lot, discovering that there was 'not much money about but plenty to eat and drink '. John Styring wrote home from Plaster Bed Sandusky Bay on March 24th 1851

The farming is very rough and slovenly compared to English farming. We have farms around us which has been sown with wheat 5 or 6 years in succession and the last is the best. There are fields in this district which produce 100 bushels per acre. They run a heavy drag over it without ploughing it and sown with fall wheat and it remains without doing anything until harvest. Animals, we have none worth speaking about only horses which are good being light and spirited, cattle are very ordinary, they take no pains in their breeding, all running about the prairies. As for wild animals most or all of them have shared the same fate of the poor Indians and have been forced to fly further west, the only remaining are foxes, mink, opossums, racoons, woodchucks, squirrels, skunks and deer etc.

Emigrants discovered an easier pace of life and a chance to better themselves through landownership. Some East Anglian emigrants were encouraged to move to the newly industrialing regions of the Eastern seaboard such as the poverty sticken emigrants who departed en mass for New York in 1830

'On Thursday last, a great number of persons passed through Bury in waggons, many people appeared in great poverty, they were from the parishes of South and North Lopham and were on their way to embark at Liverpool for the U.S.A. Between 100 and 200 are emigrating from these parishes with a considerable amount of money being borrowed on security of the rates to defray expences of passage (about 6L 10s a head) and to furnish each family a clear sum of 5L when they land at New York. Two couples from each parish married on Monday se'nnight in contemplation of joining the party of colonists and so anxious were some to quit the home of their sires, they sold off their little stock of furniture. 'Bury and Norwich Post March 31st 1830

These emigrants often found themselves worse off amongst the bad conditions, high living costs, disease epidemics and scanty employment of the eastern coastal cities. Emigration pamphlets were therefore careful to warn against this eventuality

'So many emigrants arrive at all the principle ports of the United States that there is little chance of procuring employment in them, most of the distress which has been reported to exist in America has been suffered by those who have imprudently lingered in the cities until their money was exhausted 'Mr. Souter ... and J. Knight, The emigrant's best instructor, or, the most recent and important information respecting the United States of America p11 (20-27)

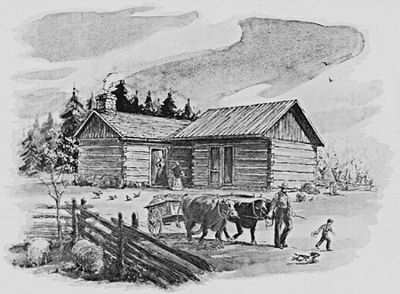

The experience of the migrant to British North America during the 1820s and 30s was for the most part positive despite the underdeveloped nature of Canada in comparison to the United States. A report of 1831 drew attention to the 'sober industrious people' emigrating to Canada where 'from the high price of labour they are obtaining a comfortable existence 'Bury and Norwich Post June 8th 1830. For many this rosy picture proved to be the reality due to vast tracks of undeveloped land at their disposal. Emigrants of 1831 informed their relatives that 'the climate seems the same as in England perhaps a little warmer, I am rich on a 100 acre block, crops look well'.

Others cheerfully reported 'we have all got places at 30s a man with board, washing lodging and 50 acres of land with nothing to pay for 3 years 'Bury and Norwich Post September 14th 1831. Canada's popularity stemmed from an extremely generous system of land grants under which even the poorest colonists could secure as many acres as they wanted even if they lacked sufficient capital to carry them to their destinations. Even after the abolition of free grants to emigrants in 1832, the system remained highly liberal. This led Lord Durham, in his report of 1838, to comment on the way almost everyone who applied for land obtained it, until it seemed as if the government's sole object was to divest itself of all control over the unsettled parts of the provinceStanley Johnson, Emigration from the United Kingdom to North America, p219 (14-16). Some emigrants had a different experience, particularly artisans seeking urban employment. John Dunn, a cooper from Norwich was unable to find work despite moving to Quebec and upon returning home wrote to the press warning that unemployed emigrants were being paid in store goods and that thousands wished to return to their home country .Joy Lody, Return of the Natives, Edp24 2002 p3 A migrant featured in a government report recognised that his lot was considerably better but lamented that 'we could be glad of a drink of could water from England or a drop of home brwed beer for thare is no good beer in Amerikey 'British Parliamentary Papers, Poor Law session 1834 Appendix A and longed to return to his own country. Government and parish officials dismissed such disparaging reports as demonstrating deficiency of character. The overwhelming impression gained throughout the early stage of emigration was that, with hard work and industry, there was no reason why an emigrant might not prosper in the New World. The possibilities of emigration were therefore strongly promoted as a possible solution to relieve the overcrowded parishes of East Anglia. These beliefs would greatly affect the mid 1830s debate on the possible reform of the existing Poor Law.

'We are in a free healthy colony, the voyage was over mighty deep waters, like a dream, although we are 16000 miles away from our birth place and friends and family'

Migration from East Anglia increased exponentially following the

introduction of the New Poor Law in 1834.

From June 1835 to July 1837, in

addition to private emigration, 3354 people emigrated from Norfolk and

1083 from Suffolk .Arthur Redford, Labour

Migration In England (1800-1850), p109 (7-19) Of the total amount

of migrants and emigrants involved in early Poor Law emigration schemes,

two thirds originated from Norfolk and Suffolk .A

Digby, The Labour Market and the Continuity of Social Policy after 1834:

The Case of the Eastern Counties, Economic History Review 28 (1975) p81

(40-41) The search for a solution to the problem of rural poverty

led the landowner-dominated Whig government of 1834 to draconian reform

of the existing poor laws. Whether as a 'sustained

attempt to impose an ideological dogma, in defiance of the evidence of

the human need 'E.P Thompson, The Making of

the English Working Class, p295 or an economically essential

experiment, the Poor Law of 1834 was highly significant in the

development of East Anglian emigration. Migration Schemes were formed to

transfer the labour surplus of the rural counties to manufacturing

districts that were short of workers. Emigration schemes removed those

who were unsuitable for factory employment .A

Redford, Labour Migration in England 1800-1850, p105-9 In The

1830s it was the emigration schemes that were to prove more popular as

they offered the possibility of land and prosperity.

Rural poverty and the subsequent burden on the rates was the subject of many passionate political tracts, which almost universally condemned the abject state of 'Pauperism' existing amongst the underemployed rural poor. The enemy was not seen as poverty (which was merely a lack of money, an in-eradicable feature of a stratified society), but pauperism, a character defect involving idleness, unreliability drunkenness etc. which led so many of its victims into desperate financial straits and threatened the stability if not the fabric of society. The difficult economic conditions of the 1830s produced an attitude of condemnation towards what was perceived as a generalised subclass of undeserving paupers, a view encapsulated in the writings of contemporary author Thomas Walker

'The whole life of a pauper is a lie - his whole study imposition; he lives by appearing not to be able to live ; he will throw himself out of work, aggravate disease, get into debt, live in wretchedness, persevere in the most irksome applications, may bring upon himself the encumbrance of a family, for no other purpose than to get his share from the parish'Observations on the nature, extent, and effects of pauperism, and on the means of reducing it / by Thomas Walker. P18 (17-23)

Political pamphlets reeled off accounts on instances when unscrupulous members of the poor had manipulated the system to which they owed their very subsistence. The phrase 'I will throw myself upon you and then you must relieve me 'Thomas Walker ibid p20 (11-12) was frequently quoted and became synonymous with the indolent poor. Amongst the landowning classes, this antipathy had been stoked by decades of rural disturbance. Resentment was coupled with traditional bitterness from landowners bemoaning the tendency of the unemployed to indulge in poaching, those 'profitable nocturnal occupations, which often procure for them many little luxuries and comforts 'Hints on emigration, as the means of effecting the repeal of the poor laws / [Anon.]. Another prevailing belief of the 1830s emerged from the influential writings of Malthus, that paupers had been encouraged to make improper marriages and breed by the very financial support that had been given in outdoor relief for the previous half century .To quote the author of 'Hints on Emigration 'It is by encouraging improvident marriages, that parochial provision so much increases population 'Hints on emigration, as the means of effecting the repeal of the poor laws / [Anon.].p15 (5-6). The rural poor were therefore widely assumed to be cynically exploiting the parish system.

These beliefs, coupled with the ever-increasing demands on ratepayers led the government to set up a royal commission in 1832 on whose report the New Poor Law was based. The commission devised a simple way to eradicate pauperism at minimum cost and bureaucratic intervention. The workhouse system would compel the indigent to reform in order to avoid conditions that were to be deliberately worse than that of an independent labourer of the lowest class. Outdoor relief was to be phased out within two years and paupers were to be made to feel like unwelcome guests. The implementation of this system sprang from the strong belief by influential figures, including the Poor Law commissioners, in the idea of individualism and forcing labourers to make their own way.

Many of the effects of the Poor Law bill were however, diluted by local forces and social policy after 1834 demonstrates clear continuities with the system that had preceded it .A Digby, The Labour Market and the Continuity of Social Policy after 1834: The Case of the Eastern Counties It had been hoped that the farmers would see the economic advantages of providing employment rather than meeting the higher cost of maintaining agricultural workers and their families in the workhouse system. However, this didn't happen.

The Poor Law system proved unpopular, badly run and easily thwarted. In the 1840s about 70 percent of the able bodied poor in East Anglia were still receiving relief outside the workhouse due to a legal loophole allowing relief in the case of disease .Richard Price, British Society 1680-1880 p179 (19-20) The Poor Law particularly hit the common labourer, providing farmers with even more opportunities to tilt the market in their favour. The domination of the Board of Guardians by farmers ensured that a free and mobile labour force could be maintained, subjected to low wages and reduced allowances. Farmers continued their age-old 'farmers shift', being content to shift the labourers backwards and forwards between the farm and the parish. Because the demands for manpower in corn growing regions were seasonal, there was a good degree of employment at harvest time. In winter the workhouses were filled, mainly with single men as married men were generally favoured by farmers due to the high cost of supporting their families in the workhouse. In the summer months when employment was high, the workhouses were used as a kind of labour exchange.

The Poor Law clearly changed farmer's attitudes towards emigration, a fact seen in the correspondence between Norfolk Magistrates and the emigration agent for Canada between 1835-37 .A Digby, The Labour Market and the Continuity of Social Policy after 1834: The Case of the Eastern Counties, p81 (1) Local magistrates such as William Mason had become 'much interested in the emigration of poor people from my vicinity, in consequence of the effect the new poor law will have on this county in our populous parishes', emigration had become a necessity because there existed 'so great a deficiency to employ 'Return and correspondence on Emigration P.P. 1836 XL, p.476 Report from the Agent for Emigration in Canada, 1836 P.P. 1837, XLII, p32 in A Digby, p82 (12-14). Farmers took the financial lead in assisting emigration, sponsoring it privately and in their capacity as ratepayers and occupiers: They were also the local administrators of the poor law schemes and participated eagerly in providing 71% of the national total of 6,403 emigrants of early schemes. Yet despite early enthusiasm, farmers by 1837 had shifted their attitudes East Anglian farmers were naturally keen to preserve the quality of their workforce and could only tolerate a small exodus of good labourers if it was in the interests of persuading inferior men to imitate them .A Digby, ibid p81 (26-28) The burden of a surplus labour force was clearly preferable to losing first class labourers. Farmers were ambivalent towards the problem of surplus labour because, as a Norfolk proprietor wrote, 'the labourers 'except during the harvest, become during the great part of the year a dead weight upon usH.Lee-Warner to Sir E Parry, 8th of August 1835 M.H 12/8596 quoted in A Digby, The Labour Market and the Continuity of Social Policy after 1834: The Case of the Eastern Counties p82 (5-7) '. A large surplus of labour was also necessary because different quantities of labourers were required every year depending on the state of the harvest. Resident full time workers provided farmers with only half of their labour force during harvest time so there was a dependency on casual and part time labour. This situation was highly precarious because few Irish or Scotch harvesters were available.

In 1837 therefore, farmers caused the collapse of a scheme financed by the government of New South Wales to assist the emigration of 30 agricultural labouring families from Wayland and Guiltcross in Norfolk, Blything in Suffolk and the Royston Union in Cambridgeshire. The aspiring emigrants were to be sent in the Orontes from Yarmouth in August of that year yet by that date opposition to losing good labourers had grown to such a degree the scheme was shelved A Digby,ibid p81 (28-29). Landowners such as Coke of Holkham were quick to remove their financial support for emigration if they felt that their good labourers were simply voting with their feet R.A.C Parker, ‘The Financial and Economic Affairs of the Cokes of Holkham, 1707-1842 D.Phil thesis, University of Oxford 1956, pp260-1

Amongst some East Anglian workers there was great enthusiasm for emigration as a means of gaining employment. In 1836 a petition from labourers in Attleborough in Norfolk stated that due to low wages and lack of work, they were 'willing to emigrate, with a good hope of bettering our situations in consequence of obtaining permanent employment for ourselves and our families 'Attleborough Poor to P.L.C 4th of May 1836, MH 12/8616 quoted in A Digby, ibid p81 (40-41). When farmers increased employment in Norfolk and Suffolk in order to retain labour, this eagerness to move disappeared. Unless undertaken through great necessity, emigration to the East Anglian rural worker was unlikely to be a popular option given the undoubted trauma involved in loss of settlement and the breaking of ties of kinship. Labourers, particularly in the south of England did not want to move far from their native place choosing to remain on land which offered full employment only in harvest time M.A Crowther The Workhouse system 1834-1929 p14 (25-38). Richard Bacon writing in 1826 on The distress of the Agricultural labourer and its Remedy refers to

'a repugnance to emigration which is only overcome generally by the pressure of extreme distress. There is the separation of families and connections and the final danger of the separation of the colony itself from the mother country 'Richard Bacon The distress of the Agricultural labourer and its remedy, p6 (3-4).

Emigration, even to the high wages and gainful employment of Canada was tainted by the stigma of transportation and a common public perception that seeking a life abroad was a risky gamble that could only lead to further destitution. The poor themselves regarded parish settlement and the right to parish relief as their birthrightK.D.M Snell, Annals of the Labouring Poor, p112, (16-17) .

An article reporting an attack of arson in the village of Toppesfield published in the Colchester gazette of May the 18th 1835 gives some sense of contemporary attitudes to emigration. The crime was almost certainly a response to large-scale unemployment, in four adjourning parishes no less than 200 able bodied men were without employ' and this in May, 'a time of year when many kind of farm work could be carried out to an advantage 'Colchester Gazette May 18th 1835 Quoted in Our Mother Earth’p146 (11-14). The gazette notes that

'the unemployed labourers had been reminded of the facilities of emigration, but alas their answer to this was a ready one. Here they had at least sufficient to maintain existence, but feared that if they went abroad they might be left to die of hunger 'Colchester Gazette May 18th 1835 Quoted in ‘Our Mother Earth’ p146 (14-17).

Even following the scrapping of Poor Law relief some were still unconvinced that a life abroad was the better option. Such mental obtuseness towards the idea of emigration by many amongst the agricultural workforce, may also have resulted from a lack of education. Uneducated people do not normally move unless spurred on by necessity. Education in the early part of the 19th century was sorely lacking and what there was of it did not include the dangerous subject of Geography Arthur Redford, Labour Migration in England 1800-1850, p95-96 (32-10). Under such conditions of doubt and suspicion, the accounts of those who had migrated before were of the utmost importance in persuading the public of the advantages of emigration.

The wider debate on the Poor Law affected emigration in the way that anti-poor law propaganda had generated wild myths about the fate of paupers to be sent to the new "bastilles". This resulted in a series of brutal attacks on poor law relieving officers in Norfolk caused by a panic born of wild rumours Nicolas. C. Edsall, The Anti Poor Law Movement (1834-44) p41 (20-25). Faced with lurid accounts, a wide variety of people became keen to leave the region for overseas regions. Many of these negative perceptions of the workhouse had much basis in fact. Conditions in East Anglia's workhouses before and after the New Poor Law of 1834 were often appaulling. The region's workhouses by the end of the French wars had become mainly asylums for the helpless poor and rarely employed the able-bodied, instead aged people and children predominated in them. Parish authorities had long given up setting inmates to work, instead dispensing outdoor reliefM A Crowther, The Workhouse System 1834-1929 . At Norwich 700 paupers were housed in a former monastry under dark and confined conditions, dormatories were crowded with as many as forty beds and the inmates were made to queue for their food and eat it on their bedNorman Longmate, The Workhouse, p31 (26-30) .Suffolk in paticular suffered problems from its large and rowdy workhouses such as the Cosford House of Industry, whose local guardian reported

'Amoung the varieties of mischief practiced by the inmates, one is to break all the chamber pots they can lay hold on: I am told they have lately demolished about forty of them. The governer refused to supply them with more and sent them a pail instead, which they pitched out the window and made use of the corner of the room in preference 'Norman Longmate, The Workhouse p84 (20-26)

In times of depression only the Poor Law stood between the worker and starvation, yet it was common for the rural poor to vent their anger on the dispensers of relief, paticularly if they were thought to be callous and mean. The workhouses and their overseers became villified by the rural poor for whom they were natural targets during times of dicontent. In 1816 in East Anglia, a rioting mob marched on the local magistrates to demand an increase in the level of outdoor relief crying 'bread or blood' In an incident that occurred during November 1830 at Forncett, the poor house was partly pulled down by rioting laborers. During a similar riot at Attlebriough affair the labourers marched on the workhouse and demanded bread and cheese from the governer .E.J Hobsbawm and G. Rude Captain Swing p158 (37-41) Attitudes towards the overcrowded and badly run workhouses of East Anglia were therefore highly unfavourable even before the draconian measures introduced in 1834. How the threat of the workhouse played upon the mind of the East Anglian emigrant is demonstated by a letter published in Bury and Norwich Post of September 14th 1831 from a Cratfield man who left for Guelph in Canada.

'my spirits are good and health much better than when we left England, I have no fear of going to the workhouse, tell my friends in Cratfield from this I was a great fool not to have come 5 years ago 'Bury and Norwich Post September 14th 1831

By attempting to force the labourer back to his employer through the ending of the Poor Relief system, the Royal Commission had forced an unworkable system on the countryside that could not solve the problems of rural society and merely added to its bitterness M.A Crowther The Workhouse system 1834-1929 p23 (12-14). Following the 1834 Poor Law Act the workhouse became a place of unresolvable tension, attempting to deter the able bodied poor yet also meant as a refuge for the ailing and helpless. Deliberate arson had long been an expression of protest amongst communities crippled by chronic rural poverty and inevitably it was used against the workhouses. As the one of the main buildings of the communitiy, workhouses became symbols of class hostility and the obvious places to attack. The overt hatred of the workhouse system that existed amougst the majority of the rural poor is shown by a report of a fire at Sible Headingham which reports that 'fire was discovered in a shed adjoining the workhouse….supposedly wilful.. during the fire some micreants threw firebrands upon the men employed in the fire Bury and Norwich Post May 20th 1835. Faced with the choice between the uncertainties of moving to the colonies and the certain horrors and deprivations of the 'Bastiles', the workhouse system represented a considerable push factor. Animosity caused by the Poor Law system led to a large forced exodus of the most deprived of the rural poor by transportation in the 1840s.

Smouldering resentment amoungst young men who belonged to the group with the lowest wages and most uncertain employment turned into active hostility and outbreaks of incendrism throughout the region in 1843 and 1844. Such attacks became so common that they led to calls to ban the sale of lucifer matches Bury and Norwich Post May 28th 1844. These were the people most likely to go into the workhouse during the winter months and consequently their anger turned towards the farmers who controlled both their wages and the poor relief. Many of the prisoners brought to justice were illiterate. As a report stated 'Out of the 63 prisoners tried only 11 were able to read and write Bury and Norwich Post August 16th 1843'; for their misdemeanors they were sentenced to transportation to Australia for 15 years. This included a boy of 11 despite having been 'Recommended mercy on account of his age ' Bury and Norwich Post, July 26th 1844. Attacks concentrated on those farmers who were poor-law guardians and where the ticket system had been implemented requiring the labourer to 'use his best exertions' to seek employment before he would be considered for poor relief. This system was brought in paticularly in areas where rural underemployment coincided with industrial unemployment caused by the collapse of the textile industry and was present in five Suffolk, two Norfolk and five Essex unions. The principle allergation against the ticket system was that it was that it was used by farmers as an economic instrument to keep wages low and could lead to the victimisation of certain labourers. The evidence that exists concerning agricultural cash wages indicates that wages in East Anglia in the ticket system period of the 1830s and 1840s declined far faster then the national average for England and Wales. Similar figures for the region show wages to be one or two shillings a week lower in ticket system areas. Furthermore the poor law system would refuse a labourer relief if he was unemployed through having refused to accept low wages as 'the board always considered that they could not and had no right to interfere between the labourer and his employer'Caxton and Arrington Return, 6th of July 1844, M.H 32/80 quoted in A Digby, The Labour Market and the Continuity of Social Policy after 1834: The Case of the Eastern Counties p78 (3-5) .

With the odds stacked firmly agains the labourer he was more likely to abandon his birthplace when given the opportunity. With the added stimulus given to the existing rural population by the Poor Law amendment act emigration was more effective in addressing the unemployment figures. In 1837 Blything union, whose severe parish bill was discussed in chapter one, was able to report that emigration had taken place 'To a considerable extent' and that the reports on the condition of the emigrants were 'remarkably satisfactory 'The Agricultural labourers, in Suffolk Farming in the Nineteenth Century, edited by J Thirsk and J Imray p138 (13). Heavy Emigration from the union led farmers to increase employment to eliminate the labour problem, however agricultural depression in 1840s produced renewed unemployment and restored the problem . As well as a way of easing the burden on parish funds emigration schemes held the advantage that they were less likely to return. In one case, the families of two men of 'desperate character' were compelled to emigrate by threats to prosecute them for felonies, which it was felt, they had certainly committed. Such a case highlights the inadequacies of transportation, were the men to be sent to a penal colony 'their families would become chargeable, which would entail a heavier expense than if they were got rid of all together'. Despite being given this reasonable option, the unwilling emigrants did not go quietly and the overseer was obliged to 'knock them off' his coach with a 'constables staff 'British Parliamentary Papers, Poor Law session 1834 Appendix A p376 (10-45). In a similar case the overseer was threatened with violence by the inhabitants of towns along his route for 'being engaged in transporting people who have not been guilty of any offence 'British Parliamentary Papers, Poor Law session 1834 Appendix A p376 (10-45). These and numerous other cases were ideal fodder for government officials swayed by Malthusian views of the poor as lazy and un-enterprising and convinced of the need to deter them from any system of parish relief.

'What a picture this observation gives of the miserable helplessness brought on by the Poor Laws, that it is necessary to watch and tend the emigrants as if they were children. It cannot be doubted that the idleness and recklessness of character which is fostered by the certainty of maintenance, drives many to the perpetration of crimes of which they might be guiltless, had they not been spoiled by dependence on the parish'British Parliamentary Papers, Poor Law session 1834 Appendix A p376 (49-52)

Those that did leave for the colonies provided glowing reports of how their situation had improved, letters that were printed in local newspapers for the benefit of the literate public and no doubt also spread by word of mouth. Such public and private correspondence was important in serving to discredit assumptions about the colonies, an example of which is the Norfolk emigrant to New York who reported that there were 'no snakes or wild animals'. Correspondence from labourer emigrants from Langham who emigrated to Australia in 1840 served a similar purpose

Suffolk and Essex Free Press, November 4th 1846 'You say the neighbours say we carry bundles on our backs and dig allotments, no we have 60 acres…we hope Mr Wilson will send out more people for many men work in the copper mines and farmers cannot get the work done. A rich gold mine has been found recently in which they are working rapidly…Dear brothers it would be well if you could come out to us, you can yet come, there is no mistake if you work well and be steady '

The contents of these published letters, often illustrated the advantages of leaving England by reeling off prices of food, beer and various other commodities, as well as the level of wages and the opportunities for employment that existed. The high price of such luxuries in Britain when compared to colonial prices must have been a significant draw. Others contributed to the exotic public image of 'Terra Australlis' by descriptions of the wildlife 'opossums, kangaroos, native cats and flying squirrels' and 'parrots in abundance which provide fine sport for the diggers who shoot them in their spare time '.Bury and Norwich Free Post, February 16th 1858 The result of the sustained patterns of emigration that had taken place before and after the implementation of the New Poor Law was the successful establishment of large numbers of people from the Eastern Counties amongst Britain's Pacific colonies, British North America and the United States. The majority had become successful, attaining land and wealth beyond what was possible in the depressed economy of 19th century East Anglia. By the 1840s their attitude towards the mother country had become positively paternalistic, as one Canadian emigrant wrote in 1847

'Meetings are held all around us and people are giving considerable amounts of money which are on their way to the old country. Thank god we know nothing of such distress here. The land of our adoption is a fruitful country and a land of plenty…We have millions of acres lying here dormant, here we have no dread of the union house or sickness and old age. 'Bury and Norwich Post, June 1st 1847

The Poor Law reforms did not significantly alter the existing system of parish relief. The Poor Law did however increase the amount of assisted emigration and many workers cognisant of the advantages of moving overseas were willing to take such a step in search of employment. By the late 1830s's emigration had become such a powerful movement that parish authorities were forced to veto such schemes due to the threat to their labour pool. Workers in general were prepared to remain in the region if they were provided with some kind of subsistence no matter how meagre, unwilling to separate their ties with the region. The second half of the century was to see a change in attitude. Invigorated by ties of kinship and popularised by the growing belief in the potential of Britain's colonies, emigration was to become a popular movement for both labourer and farmer alike, despite improvements in East Anglia's rural economy.

Emigration continued unabated during the 'golden age of farming ' Despite a revival in its fortunes, the countryside was still characterised by disharmony and disruption that provoked young men into migrating or emigrating in search of higher wages. Wages rose during the golden age yet they did not rise as fast as the price of food, with meat in particular remaining expensive. The general increase in labourer's wages did not increase his standards of living. Farm workers, particularly in the south, were among the most poorly paid in the country, receiving about two thirds of the wages of their town counterparts, although some were able to supplement their meagre wages with piece-rates for such jobs as hedging, draining, mowing , turnip-hoeing and harvesting. Peter Wormell, The Countryside in the Golden Age of farming p69.The fact that the prosperity of farming did not reach the labouring classes is aptly illustrated by the fact that some 377,000 hired workers left the land in England and Wales from 1851-1881 with an average annual exodus from the villages of 75,000 over the same period. The living conditions of the East Anglian labourer continued to be appalling, as shown by a report of 1871 by Julian Jeffreys on the employment of women and children in agriculture that was commented on in the local press

'The average dietary of the labouring population in rural areas in Southern England may be described as following-beef and mutton was rarely tasted so that they do not form part of their diet….Bread and cheese forms the main part of the diet for adults, the poor mans cow being a blessing of the past as milk does not or rarely forms much part of the diet in village children, even in infancy….I know a large parish in Suffolk mainly dependant on ditch water in certain seasons the administations of vermifuge would expel from the bowels of perhaps half the children, worms many inches long. 'Bury and Norwich Post, March 14th 1871

Emigrants who arrived in the colonies discovered both a higher standard of living and an impovement in social relations, something that became a priority given the poor relationships between employer and employee in East Anglia.

Emigrants letters from settlers in Canada and South Australia collected in the parish of Banham Norfolk 1852, in K.D.M Snell, Annals of the Labouring Poor p13 (22-24) 'Master and Mistress and all the family sit at 1 table and if there is not room at the table for the whole family to sit down, their children sit by till workmen are served; there is no distinction between the workman and his master, they would as soon shake hands with a workman as they would with as gentleman '

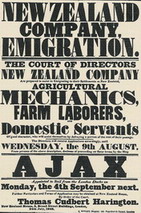

In 1848 the New Zealand Journal had proclaimed that 'It is impossible not to be struck with the important feature which emigration now forms in the metropolitan and provincial Journals; some even devote a weekly column to information gathered from the numerous books guides and brochures that swarm on the subject 'Jill Kitson, Great Emigrations : 2 The British to the Antipodes, p80 (31-32) In the 1840s and 50s, as assisted emigration gathered momentum, there was an explosion of emigrant guides tracts, pamphlets and newspaper articles appealing to a wide range of people. This wide circulation of advertisements for emigration suggests that contemporary officials expected a high degree of functional literacy from the labouring classes. With so many emigrants processing the ability to read and write they were better able to make a more informed choice concerning their destination. As the century continued, the growth of the railway network, the arrival of cheap newspapers and the general improvement in internal communications made country people more aware of the economic and social choices available beyond their own parish.

Source for table Idigent Misfits or shrewd operators? Government assisted emigrants from the United Kingdom to Australia 1831-1860 by R Haines Population Studies 48 p234| % of total emigrants | New South Wales (1848-60) | Victoria (1848-56) | South Australia (1854-60) |

| Cannot Read | 19 | 16 | 21 |

| Read Only | 22 | 20 | 23 |

| Read and Write | 59 | 64 | 56 |

Organisations such as the non-conformist Religious Tract Society produced material specifically aimed at encouraging the working classes to emigrate. By the 1850s emigration as a movement had broadened its appeal, it was no longer just a labourers method of escaping the low wages and uncertain employment of rural life. To the struggling farmers and bankrupt businessmen of East Anglia it had become a way of making a quick fortune in the emerging colonial markets. Increasingly the middle class farmers and professionals were confronted by the prospect of a loss of status through economic hardship and were increasingly drawn to seek their fortunes overseas.

Although North America remained the most popular destination for migrants from the British Isles, the Antipodes emerged as a powerful draw for English migrants, in particular those who lived in low paid agricultural regions such as East Anglia. In 1857 for instance, 76 percent of agricultural labourers chose Australia as their destination, dwarfing North America's share of that year.Idigent Misfits or shrewd operators? Government assisted emigrants from the United Kingdom to Australia 1831-1860 by R Haines Population Studies 48 p233 (The Eastern counties are defined in Baines research as being Huntingdonshire, Cambridgeshire, Suffolk, Norfolk, Lincolnshire and Rutland.)

The growing popularity of Australia reflected its attraction for those of the agricultural workforce who wished to avoid industrial occupations in Britain. Newspaper reports such as the Bury and Norwich Post, November 14th 1848, described the country as 'the land of promise and descriptions of their experiences sent back by emigrants and published in the local papers served to build up an impression of Australia as a Garden of Hygeia where the rural poor could proper physically and spiritually. The sense was that a pastoral environment such as Australia offered more opportunities to become self-sufficient, a tempting prospect given East Anglia's comparatively draconian system of labour. As one letter gloated

'This is winter here but I am working in my shirt sleeves, no sending back if you are a few minutes late for here Jack is his own master. Hope the rest of you will follow me 'Bury and Norwich Post January 2nd 1856

As a pastoral nation in contrast to the industrialising United States, Australia had more draw for the rural emigrant who chose overwhelmingly to take the voyage to the Antipodes when the cost of the voyage was equal to the Atlantic crossing. One factor in this decision appears to have been that the main port for travel to the United States was Liverpool whereas the ports offering the most passages to Australia lay in the South, within easier reach of the eastern counties.

Robin Haines, Indigent Misfits or shrewd operators? Government assisted emigrants from the United Kingdom to Australia 1831-1860 by R Haines Population Studies 48 p234 (low wage agricultural regions include (Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Devon, Dorset, Berkshire, Essex, Herefordshire, Hertfordshire, Hampshire, Huntingdonshire, Norfolk, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire, Rutland, Shropshire, Suffolk, Somerset, Suffolk, Surrey, Wiltshire.)| Australia 1846-50 Government Assisted Departures | New South Wales (1848-55) Government Assisted Emigrants | United States Ship Lists Males Only (1846-54 | |

| % of total emigrants from low wage agricultural regions (Includes Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk ) | 44.2 | 57.1 | 24.3 |

| Total English Emigrants | 29,378 | 25,849 | 608 |

A major draw to the Antipodes was the discovery of Gold in lodes, firstly in New South Wales and then most significantly in Victoria to which region 290,000 people migrated from Britain from 1852-60.Geoffrey Sherington, Australia’s Immigrants p27 (12-13) With the news of the discovery of Californian Gold in 1848 the public of Britain were already suffering from Gold Rush fever. Australia's gold discoveries held more attraction for potential diggers because they had taken place in a country where the rule of English law prevailed and involved a less torturous journey than that to America's west coast. From middle of 1851 when word of Hargraves' discoveries reached Britain, it seemed that almost every ship arriving from the colonies brought word of new and richer gold finds. Australia's advantages and its favourable prospects for active young Britons were well publicised in Charles Dickens's articles in his periodical Household Words. East Anglian emigrants such as Henry Ruse tapped into this spirit of excitement, the discovery of gold holding out the prospect of instant and seemingly limitless wealth, capital that could provide a future living,

'I suppose you saw the letter I sent to Thomas about my going to the gold

diggings. I should like to go there again now, if I had a pal to go with.

There are many who make a fortune in a very little time. I wish I had a

little more money. I would take a windmill. There is one to let, there is

plenty of profit 'Bury and Norwich Post, March 2nd

1853

From the Essex village of Thaxted alone, nearly 100 working men left their jobs to begin the hazardous sea voyage, a journey o fifteen to twenty weeks or more, depending on wind and tide conditions. Even the best sailing ships were however, subject to extreme difficulties on such a long voyage. One prospector from Coggeshall who travelled to Australia on the Bangalore wrote that

'On the 11th day of August, a heavy sea striking the vessel carried away our starboard bulwarks, and almost sent the longboat and the cooks' galleys overboard ; the water poured in and flooded us below, and a great many thought we were going down . . . the poor fellows down below are in an awful state, their beds wet through, and almost swimming in their cabins.'

Upon arriving in Australia, emigrants faced the chaos of gold fever. Life in the towns neighbouring the goldfields was brought to a standstill, everybody having rushed off to the diggings, leaving shops, factories and government buildings unattended and the farmland untilled. Only the elderly remained. An Ingatstone man wrote that

'During one week Melbourne seemed like a city of the dead, the usual busy hum of trade was hushed, the mills were stopped, the foundries were still, all labour ceased, and the innumerable buildings in progress were stopped."'

The hordes of eager prospectors only had to pay the government fee of thirty shillings for the right to dig plots measuring eight feet square. They were however, forced to pay exorbitant prices for horses, tents and mining equipment. Despite this, huge numbers of people descended on the diggings. At Golden Point, during 1853, a Colchester man reckoned that there were nearly 5,000 people at the diggings, the scene resembling 'an ant-hill on a fine summer day.' As many were to discover, reaching the diggings did not automatically guarantee financial success According to an Ingatestone man 'a man could go down to his hole penniless in the morning and come out at night a thousand pounds richer ; while his neighbour, only one foot away from him, would sink his hole twenty or thirty feet deep and find nothing.' As well as the uncertainties of life on the diggings, the prospectors also had to endure a primitive existence without comforts or amenities. Another Colchester prospector who moved to Melbourne in February 1853 wrote that

'drawing your own water, cutting your wood, lighting your fire, boiling your own kettle, getting your meal just anyhow, and then rambling off with your gun under your arm in search of wild duck and opossum-all this is very primitive and pleasant ; but rain and dust and cold, and having to clean your own boots, and to take a willow-pattern plate to the butcher for chops-these little annoyances make you once more fight for civilization.'

East Anglian migrants also had to cope with rampant lawlessness. One Essex man explained in a letter reprinted in the Essex Standard for April 9, 1852 that 'The police are insufficient to protect the industrious diggers from the vagabonds who surround them ; and all are arming themselves for the protection of their property and lives.' Another disillusioned emigrant described the inhabitants of Melbourne as

'a murderous, drinking, swearing, stealing, greedy, grumpy, ugly set of people. . . . My first night on Australian soil I spent walking up and down as a sentinel before our tent, beneath the bright watching southern stars, with my meerschaum in my mouth and a revolver in my pocket.'

Success at the diggings could be short lived amidst such a prolific crime rate. Most robberies took place in the towns where the successful prospectors provided ample evidence of their newly found wealth. A Colchester man sadly referred to a digger who had made between £400 and £500 but lost it all

'he foolishly spent and got robbed of nearly the whole of it. ... As to the chances of you having your gold stolen from you after you have worked hard for it, I think that nineteen out of twenty robberies that are committed are upon drunken persons who have foolishly exposed their riches in a public-house.'

For the successful, champagne-sometimes mixed with rum " to give it piquancy "- became the order of the day ; and the inevitable drunkenness went hand in hand with all forms of debauchery and vice, leading the Essex Standard in 1853 to report that 'the newest diggings in particular are the hotbeds of licentiousness and crime' Sudden wealth also generated the occasional riotous celebration,

'It is the intention of about all the diggers to visit Melbourne at Christmas, and judging from the present state of the town I should not be surprised if it were burned to the ground, as the few who have returned are determined to drink it [their wealth] freely, and have a spree.'

The unsuccessful found themselves penniless and were often forced to take up work as labourers when the gold rush ended, forced into lower wages by the overstocked labour market. After a few years some of the disappointed treasure hunters managed to save enough money to return home. Other colonists were slow in grasping the respective benefits of the lands they had adopted. In the early 1850's John Cody, a Suffolk farmer, decided to become part of the Anglican settlement at Canterbury New Zealand. However he like many settlers initially subscribed to Wakefield's belief in an agricultural settlement rather than one based around sheep farming, which was recognised by one visitor to the colony in 1851 as 'the only source of its prosperity '. Commenting on his brother's move to New Zealand Charles Cody was to say 'It appears to me a hasty step and ties you to a certain locality when you might hereafter hear of others offering greater advantages. We hear of Gold Mines now-a-days and nobody knows what'.Suffolk Farmers at Home and Abroad, in Suffolk Farming in the Nineteenth Century, edited by J Thirsk and J Imray, p164 (2-3) Emigration by the early 1850s had therefore lost much of its earlier stigma, no longer merely a moderately successful experiment in combating rural poverty. The experience of other migrants and reports of success from the colonies had resulted in the emergence of Emigration as a popular movement. By this stage communications with the colonies had improved to the extent that reasonably well off farmers were able to overcome the isolation of such far off settlements. In the case of John Cody, they were even able to order new agricultural equipment through their contacts in the 'old world'. His brother was able to report, 'your desire for one of Ransome's Y.L ploughs having been communicated to Mr. Sam Toller he has more kindly commissioned one 'Suffolk Farmers at Home and Abroad, in Suffolk Farming in the Nineteenth Century, edited by J Thirsk and J Imray, p165 (41-43). With the switch to sheep farming John Cody was able to become prosperous in contrasting circumstances to many of his brothers acquaintances. By 1862 Charles Cody's reservations about his brother's move to New Zealand had been overcome and the prospects of a life in Zealand had become more appealing than those amongst the uncertainties of life in East Anglia

'I should think you are likely to have plenty of British settlers. The year of 1860 from its extreme wetness was most disastrous to all heavy land farmers. At the same time the competition for land is so great that young men generally would be wise to seek their fortunes in one or other of our colonies 'Suffolk Farmers at Home and Abroad, in Suffolk Farming in the Nineteenth Century, edited by J Thirsk and J Imray p169 (32-40).

In this event, local ties were important and men like John Cody were to play a role in familiarising newly arrived emigrants to their new surroundings, 'two of Mr Seaman's sons intend starting for New Zealand immediately and wished me to give them a letter of introduction to you '.Suffolk Farmers at Home and Abroad, in Suffolk Farming in the Nineteenth Century, edited by J Thirsk and J Imray p169 (5-9) The emigrants of the 1850s were able to draw on the first wave of people who had gone overseas earlier in the century and in some cases were able to persuade others to emigrate with them due to their connections. An example of this occurred in 1854 when the local paper reported 'On Friday last, 15 more emigrants left Great Thurlow at 3 in the morning. The principal person is a mechanic who has large family connections there 'Bury and Norwich Post, September 27th 1854. Other emigrants recognised the opportunity they had been given and were willing to help others reach the colonies. An emigrant letter of 1855 wrote 'give my duty to Mr Dunlop and ask him to thank the gentlemen who subscribed for me…if Robert would like to come let us know and we shall pay his fare 'Bury and Norwich Post, July 18th 1835. Later these ties became of even more importance as under nomination schemes the friends and relatives of colonists would gain assisted placements following the payment of a deposit in the colony or the purchase of land. This scheme accounted for thirty percent of emigration to Australia between 1848 and 1900. Emigrant reports from Australia were not all positive, especially for those who through occupation ventured out into the wilderness of the Australian interior and were bemused at the difference in culture between old England and their new environment, one emigrant wrote from Clarence River in 1854 expressing his horror at aboriginal culture

'We are all up in the bush but we don't like it here, we live in a house alone with mountain all around, all we see is blacks, sometimes we have 10 in the house at a time, they go naked and lay down and sleep….they also fight for women and they that win have the most 'Bury and Norwich Post, January 11th 1854

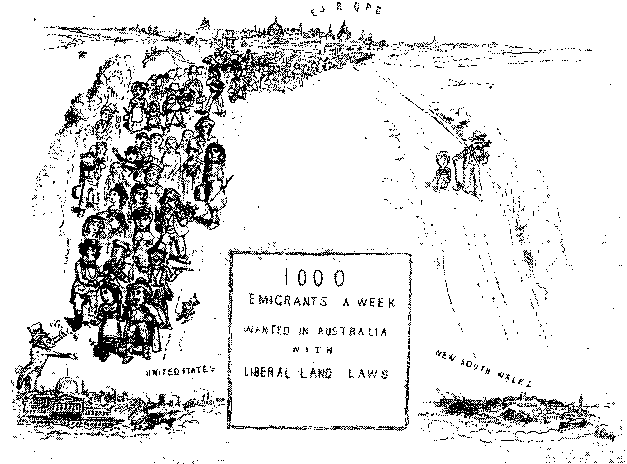

By the mid 1870s the period known as the golden age of farming came speedily to an end. East Anglia's lands were costly to cultivate and not easy to adapt to other systems of management, in the event of low prices profits were extremely hard to make. From 1875 until 1900 farmers were hit by bad harvests with the worst being the black year of 1879. Earlier in the century the Corn Law repeal had been an axe waiting to fall on British agriculture, delayed in its impact by wars in the countries of foreign competitors. In the mid 1870s the unrestricted import of foreign produce resulted in low prices while labour efficiency continued to decline as the best workers migrated or emigrated. Hampered by the inefficient railways system and bad weather, farmers and landowners were forced to give up their occupations and the countryside emptied of its gentry and nobility. By the 1870s and the beginnings of a new depression in agriculture the workers had become overtaken by an increase in confidence; far more ready to make a break with their land than their less educated parents had been. They migrated to the towns in their droves while those that remained joined the burgeoning trade union movement, in no small part due their standard of living. These increasingly militant movements were to be closely tied to the cause of emigration. Early trade unions in the south of England took on the slogan "Emigration, Migration but not Strikes" and organised the movement of workers in order to improve their lot while raising wages for those that remained.

The National Agricultural Labourers Union began to make emigration and migration central to its policies, exploiting the desire of young labourers to escape the farm.A.Brown, Meagre Harvest p42-50 It was hoped that this would lead to a long term reduction in the labour supply and therefore put pressure on employers to settle individual wage disputes. The Union’s policy of organised emigration had first been mooted in early 1873 at meetings in Pebmarsh and Stisted. In June, a meeting at Writtle was told that six nice lads'; from the village were already on a boat for Queensland. Rural agitators such as Charles Jay took up the cause, visiting numerous villages in Essex to address farm workers on the advantages of joining the Union and promoting the possibilities of emigration. Jay had worked in North America where he had witnessed slavery before its abolition and had sympathised with the wrongs of the Indians. He had returned to Britain in with a reforming mission and devoted his considerable energies to building the union in Essex. In his capacity as emigration agent of the Queensland government he was to persuade many that upon arriving in Australia they would find higher wages and more pleasant living conditions. Jay toured central Essex, on one occasion speaking from the Shire Hall steps at Chelmsford. In keeping with the biblical rhetoric of many unionists of the time, he presented Australia as a ‘promised land’ of opportunity. In August Jay announced that ‘on the 12th twenty five leave Essex for Queensland; on the 26th some more will go’ and claimed that ‘I am now inundated with applications from Essex to emigrate’. Such departures aided the union’s cause because they were presented as reluctant yet enforced renunciations of their homeland by labourers no longer able to tolerate poverty and subjugation. The Essex Standard of 1972 noted

‘The Condition of the agricultural labourer is as bad as it can be. He toils like a slave, lives like a pig and too often dies like a dog, with no pleasure but an occasional debauch at the alehouse, no prospect but that of the Workhouse for an old age of rheumatism and misery'

Essex Standard 1872 quoted in A.Brown, Meagre HarvestAs the Suffolk lock out of 1874 spread to Halstead and the Birch area, strikers in the union’s North Essex Committee brandished the opportunity of emigration in its address to its members

‘If your native land spurns her sons of toil, you have courage enough to cross the broad seas in response to those who would gladly welcome the peasantry of England. Queensland and New Zealand will gladly receive you . . . Shake the dust from off your feet and for ever bid farewell to the land of your oppression.’Halstead Times 4th April 1874 quoted in A.Brown, Meagre Harvest

Villages such as Little Maplestead that had vigorous branches of the union, saw dramatic population decreases, although many of the vacancies on little Maplestead farms were filled from nearby villages where the unions policy had been less successful. A report from Little Dunmow claimed

‘Sign of the times. Little Dunmow is a small parish. In 1871 there was a population of 359 and there is said to be less now – in fact, only a few old men and boys left to do the work…The boys will be off as soon as they get big enough and the farmers daren’t say a word to the old men as they would go now’

English Labourers Chronicle 10th of October 1878 quoted in A.Brown, Meagre HarvestA union supporter, J.V Braddy noted the effect of emigration and migration on employers. Having heard a conversation where a Kelvedon farmer had anxiously questioned one of his farm boys about the number of local labourers who were intending to move, he concluded

‘This shows that emigration is most dreaded by farmers of all the operations of the Union. It is almost entirely owing to our emigration work that the improvement of the labourer’s position has been attained. And for the dismal comfort of that farmer I may inform him that applications have been made to me for passages to South Australia and that both Mr Jay’s advocacy of South Australia and Mr Thorne’s of Canada are being responded to with the liveliest interest by the labourers all around’

English Labourer 5th of February 1876 quoted in A.Brown, Meagre HarvestSome members of the clergy tried to convince their clergys to remain in their parishes. The vicar of Southminster refused to sign certificates needed by emigrants and the vicar of Kelvedon told his congregation that ‘a man who leaves his home is like a bird that has wandered from its nest’

In what was seen as the crowning achievement of the National Agricultural Labourers Union, an entire ship ‘The St James’ was chartered and filled with 3 hundred people from Suffolk and Essex, sailing to New South Wales on April the 14th 1874. Jay toured Essex branches offering free passages, free kit and grants of £1 per man, 10s. for a wife and 5s. for each child. Parties were formed in a number of Essex and Suffolk villages, supported by collections at religious services and socials. On a morning in April 1874 they converged on their nearest railway station to board the train for Tilbury, where the Saint James was waiting to bear them away. Jay described the scene at Witham:

‘On the 14th inst. some of the finest peasantry of the Eastern Counties joined the Saint James for Queensland. It was a remarkable day in the Eastern Counties; every station from Woodbridge in Suffolk had passengers for Queensland. Kelvedon was rather a big gathering, but at Witham junction the largest party came together, some from Braintree, some from the Dengie Hundred and some from the neighbourhood around Witham ... It looked as if the Royal Family must be expected at Witham, every available space was filled by people come to see some 200 working folks leave the country. Cheer after cheer came from the onlookers and the starters; for miles from Witham every cottage seemed to expect the train to pass, for someone was prepared to wave a parting flag; hedgerows seemed to contain human beings for the purpose; ploughmen stood still and waved their hats, and at farm houses the servant appeared either at the door or window and excitedly waved her flag. At the county town it will not be soon forgotten, and masters and parsons will be more persistent than ever in refusing to sign any emigration papers. Long streets in Chelmsford command a view of the rail; they were quite alive with women at the doors waving their parting flag.’