The well-tank bothers me.

'Of demons in the dry well,

That cheep and mutter,

Clanging of an unseen bell,

Blood choking the gutter

Of lust filthy past belief

Lurking unforgotten,

Unrestrainable endless grief,

In breasts long rotten

from The Haunted House, by Robert Graves

Although Harry Price's book 'The End of Borley Rectory' gives the impression of being a mere scrapbook of evidence, it contains a powerful story. The evidence is laid before the reader and suddenly, a mass of disconnected facts fall into place. The story is a wonderful one, given its ultimate form in the recent book by Eric Liberge, 'Tonnerre Rampant'. The story goes something like this:.

'Marie Lairre, the unquiet spirit of a Nun, haunts the place, desperate to communicate to the living the need for a Christian burial on consecrated ground. She uses every trick her dwindling psychic energy can muster to alert the living to the location of her bones and the need for a burial and Requiem Mass. The communications are misconstrued and poorly understood but, finally, through the brilliant intervention of a theologian, Harry Price locates the bones, arranges the burial, and peace descends on the area.'

It is a powerful story, owing something to Oscar Wilde's 'The Canterville Ghost'. Harry Price had always maintained an amused scepticism towards Borley Rectory from the time of his first visit in 1929 until Sidney Glanville joined the team of investigators. Sidney Glanville was a neighbour of Harry Price in Pulborough, and was once described by Connie, Harry Price's wife, as being Harry Price's best friend. It was the latter's careful and methodical researches, which eventually persuaded Harry Price to change his mind, and admit that there might be something in the haunting. As Price once remarked casually to a local man 'I used to think it was all one hundred percent bunkum, but now I think it is only ninety-seven percent bunkum'.

The Glanville family were newcomers to the art of the séance and planchette, but they took to the art with gusto, producing innumerable sessions recorded on rolls of wallpaper (the spirits tended to have large writing when communicating via the Glanvilles). On several occasions, the spirits urged a dig in the cellars. The story developed that the nun was called Marie Lairre (not, surprisingly, the Evangeline Westcott who had revealed herself to the Marks Tey Spiritualist circle). Glanville never took the planchette sessions seriously and was adamant that he was completely sceptical about the 'automatic writing' that produced the identification of Marie Lairre.

"The results we obtained seemed to provide us with a clue to the nun's identity and a clue to where her remains might be buried. It seemed obvious that her unhappy spirit was seeking help. By the bye, an analysis of records show that manifestations were strongest when there were women in the rectory. Everything pointed to the restless spirit of a woman seeking escape from what one might call a spiritual imprisonment, into which some event in the past had plunged her. And it was to my daughter that one of these appeals came; it was in October 1937. She had never used planchette before. The pencil wrote the name of Marie Lairre, where she came from, and when she died. Indeed the story which we obtained from long and exhaustive sittings, over a matter of months was this:- Marie Lairre, a young French nun from a convent at Bures, not far away, was murdered by one of the Waldegrave family in 1667."

Sidney Glanville, interviewed on 24th June 1947 at Broadcasting House by the BBC

Harry Price, during the same interview, added his own elaborations

"A young French novice comes from her nunnery at Le Havre; rests for a while at a similar establishment at Bures near the rectory, gets involved with and is removed by one of the young Waldegraves who, for some reason we don't understand, murders her by strangling. The novice - wherever her spirit rests - appeals by means of the manifestations you have heard about for a Christian burial, and being a Roman Catholic wants a requiem mass said for her, incense, holy water and above all prayers. I have just received confirmation from an investigator of mine that Mary Lairre did live in the 17th century, and that she did come to England. I find this circumstantial evidence very strong - I might almost say conclusive."

Harry Price, interviewed on 24th June 1947 at Broadcasting House by the BBC

Curiously, within a short space of time, Glanville was writing that he placed no faith at all in this material, believing that these messages merely originated in the subconscious minds of the operators. He wrote that he did not believe that any such person as Marie Lairre ever existed and deplored the fantastic theories which were then built up around her. (BORLEY RECTORY Glanville, S.J. 1953). He had a point; despite considerable effort by Price, no such a historical figure was ever discovered, and it is even doubtful as to whether the original séance message actually spells 'Marie Lairre' at all.

When the first book, 'The Most Haunted House in England', had been published, the photographs of the wall writings proved to be of enormous interest. The gentry of England were fascinated by spiritualism at the time. In Suffolk, the magnificent site of Sutton Hoo was discovered in the grounds of a grand house whose owner, Mrs Pretty, had had a dream that revealed the existence of buried treasure. The wife of the owner of nearby Kentwell Hall was digging fruitlessly under the floorboards of the Great Hall in response to séance information. An eminent cleric, Dr Phythian-Adams, picked up the book on his Christmas holiday and saw, in the photograph of the wall writings, the same message 'well tank bottom me'. From this, and the séance information he constructed an elegant and elaborate theory that aimed to provide a comprehensive explanation for all the events at Borley Rectory. A Christmas diversion became a mission statement for poor Harry Price; a revelation that he had perhaps been wrong to hold the whole Borley saga at arms-length. Without this Christmas analysis, the second book would probably not have been written.

Harry Price was later very reluctant to admit that his former scepticism had been melted by the work of Glanville and Phythian-Adams. He seemed to have been rather ashamed about the change in his personal beliefs about the goings-on at the rectory, and did what he could to cover his traces. Unfortunately, he failed, and consequently fell victim to the greater charge of duplicity. In fact, the mischievous, hot-tempered sceptic who played practical jokes on the gullible cast of the 1929 'haunting', and exposed the pranks of Marianne in 1932, had declined into a sombre and worried old man of declining health, trapped by the success of his Borley writings, and brooding on his own mortality.

He said to me,

"I mean is there an afterlife in which good is rewarded and

evil punished."

I said to him that if you look at Borley from some aspects, it looks that this is the

case.

Then almost to himself, he said,

"If that's the case then we are all in a weak position, now

."

Mrs C.C. Baines, in the draft of her manuscript for the Third Borley Rectory book

The opinions of Glanville and the theologian fell on fertile ground, and the second book astonished those who knew Price well, for its uncritical belief that the events at the rectory had a supernatural cause. This was the same man who had written in 1939...

'I am notoriously not a Spiritualist, so do not belive in spirits in the spiritualistic sense. Also, she (Dr Fairfield) tries to make out that I believe in the legend of the nun. Well, I do not. '

letter from Price to Canon G.H. Rendell, Dedham, Essex, dated 28th April 1939

...though one might expect it of a man who spent ten years as a leading light of the London Spiritualist Alliance.

We owe our knowledge of the wall writings to Sidney Glanville., one of the most likeable of men. He had applied himself with huge energy to the questions of Borley Rectory. For Sidney, coming at the problem afresh, it was a most wonderful puzzle, and he applied himself with relish to the task of its solution, sweeping all with him, even his family, with his charm and energy.

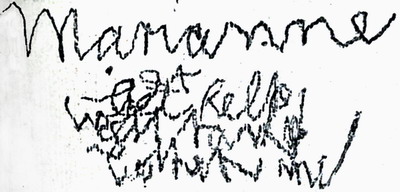

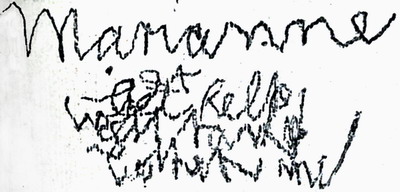

The Wall writings were a fascination for him. They had 'appeared' in the spring and summer of 1932, during the time of the Foyster residency, but were, surprisingly, still visible on the bleak undecorated walls. He traced them, photographed them, measured them, plotted them and documented them. They were tantalising. Amongst the strange meandering scribbles were names, strange appeals of 'Light mass prayers' and 'get help'. Some other messages were more difficult to decipher, and every expert that was given the task, came up with a different meaning. Edwin Whitehouse, the highly-strung nephew of the churchwarden, interpreted one message as 'Mass By Boy'; as he was in the process of taking religious orders, and had been nicknamed 'boy' as a child, he took to this interpretation with enthusiasm. Unfortunately, wiser and saner opinion read the message more obviously as 'Mrs Foyster'.

Sidney Glanville, joined by the enthusiastic Kerr-Pearse, decided to tackle one of the most difficult messages, the one that Lionel Foyster recorded in his journal

Later still, further along the passage was written 'Marianne get help (something undecipherable) bother me' (or bothers me). Marianne wrote underneath 'I cannot understand, tell me more. Marianne'. Something was added underneath but subsequently written over.

Lionel Foyster Diary of Occurrences June 30th 1931 p25

The message was, by that time, very faint, having resisted various attempts at erasure. However, they determined that the message actually read 'Well tank bottom me'. Harry Price noted that, if Kerr-Pearse was right, the message 'appears to direct investigators to look in the well'.

For some reason, the investigators thought that a 'Well Tank' would be in the cellars, and whole chapters of books have been written that maintain this misunderstanding. This is an elementary mistake. Well Tanks are never ever in cellars. To understand why one does not get well tanks in cellars, one needs a brief dissertation on the plumbing of Borley Rectory. Fortunately, I was honoured to make the acquaintance of the plumber who maintained the system at Borley Rectory in the 1930s, so I can relate this with some authority.

Borley Rectory had been built with fairly primitive plumbed 'running water'. There was a well in the courtyard and a cast-iron pump in one of the arches of the south wing. This was worked regularly and pumped the water up into a galvanised steel tank in the attics. This tank was called a 'Well Tank'. This gave the required pressure to provide 'tap water' to the kitchens and utility rooms as well as the bathroom in what later became a chapel. When the water started to run out of the overflow pipe, one knew one had pumped enough.

When water stopped coming out of the taps, it was time to go out into the courtyard and pump some more, accounting for some or all of the strange footsteps and groans heard at night by visitors. When the pump was worked at night, the lantern, according to Mr Mayes the gardener, used to produce the 'light in the window' that was often seen at the rectory.

The Smiths were horrified by the antiquity of the plumbing system, and so they created a new and splendid bathroom in one of the redundant bedrooms. In this new bathroom was a water-cylinder and airing cupboard. The input to this was from the well tank in the attic and the output provided the hot water for the taps. It was heated by an indirect system from the kitchen stove, a coal-fired 'Ideal Cooknheat' system rather like an AGA. If the water ran out, then one had to 'man the pump' as soon as possible as the water-jacket in the 'Ideal Cooknheat' that heated the water would be wrecked if it ran dry.

The well tank was, therefore in the attics, or roof space, above their heads, not in the cellars.

Harry Price became very confused about the wells, sumps and tanks at Borley Rectory. The foul water went to a cesspit somewhere in the garden 'some distance from the main building' (1938 inventory and valuation). There would have been a hatch and cover to allow access. This tank should have been emptied occasionally but this horrid task was usually neglected. There was a deep well in the courtyard that provided ample drinking water. Because the well went into the chalk and produced very 'hard' or alkaline water, the rainwater off the roofs was collected for irrigation. This was called 'soft' water, and was held in a soft water tank or cistern. Because the rectory was necessarily built on impermeable clay, the cellars were sometimes damp and occasionally flooded. In most houses of this type and size, there would have been a fairly large culvert to drain the cellars into a ditch downhill. This was occasionally discovered and mistaken by the imaginative and romantic residents as tunnels. Occasionally they became rat-infested and were bricked up, becoming, in the imagination, secret tunnels. There are some reports that the culvert at Borley rectory once had an iron grid covering it to prevent the ingress of rats. Occasionally, in wet weather, the cellars had to be drained. In order to achieve this, there was a sump, which was a shallow well with a bricked base. Any surface water in the cellars drained into this. The sump was, in turn, emptied by a small hand-pump mounted on the wall of the courtyard.

Harry Price confused matters by saying that there was a number of wells. This is because the local dialect word for a Storm-water culvert was a 'wellum'. When he interrogated local people about the tunnels and wells there was a great deal of misunderstanding due to language-differences.

In answer to the entreaties of the wall-writings, Kerr-Pearse and Glanville decided to excavate in the cellars, and unsurprisingly found nothing. They investigated the trough in the cellars, but it had been filled at some time with various waste materials.

Price adds the rather puzzling sentence

It is possible to enter the cellar from the courtyard via this tank, though it would be an unpleasant business. Observers were warned against this and so kept cellar door (leading into house) locked, or sealed; or both.

Harry Price; The Most Haunted house in England p207

Price is here describing the sump, which he excavated later on in 1943 and discovered a silver jug and a brass cooking pot. It also had a brick bottom and was a full six-foot deep. This sump was under the second entrance to the cellars; the wooden stairs that led out from the cellar straight into the courtyard. This was covered with a hatch in the courtyard, and was used to get wines and other bulky provisions into the cellar. However, Kerr obviously was tackling the pit or trough which, according to Price, subsequently disappeared. This was what they all mistakenly referred to as a 'Well Tank'. Kerr-Pearse, in his report to Price re 3 August 1937 described how he partially emptied the 'well tank' in the cellar but found nothing but old tins, a broken glass, and pieces of brick (MHH, p. 207). There was no deep well under the 'well tank', which was simply a shallow rectangular trough lined with concrete and therefore of fairly modern construction (EBR p. 260). Kerr-Pearse was rather too conscientious in making good the cellar floor because Price failed to locate it when he started his later excavations, and unintentionally did his new excavations in the same spot.

If the message really did have the improbable interpretation of 'well tank bottom me' then the spirit was actually buried underneath the well tank in the attics, an unlikely interment that would have had all sorts of unsanitary consequences.

Kerr-Pearse and Glanville also investigated the well, at some risk to life and limb.

Kerr-Pearse next examined the main well in the courtyard and actually descended to the first platform, eight feet down, by means of the supply pipe. However, this pipe was so slippery that further descent would have been dangerous, if not fatal. He found the platform very rotten

Harry Price; The Most Haunted house in England p207

Onto the scene then came 'Captain' Gregson, intent on exploiting the interest in Borley Rectory by opening some sort of commercial enterprise there. He had bought the rectory with a borrowed £500 and it had burned down under mysterious circumstances soon afterwards. His attempts at a tenfold profit by over-insuring did not succeed, but he was determined on a return for his efforts. From nowhere, he created several myths, including one of the 'missing church plate'. Ignoring the difficult fact that such things were always well-documented, he urged all and sundry to start digging in the ruins. With increasing pressure on Price to organise a dig at Borley, it became more and more difficult to rely on his innate wisdom that told him it was nonsense.

Price hadn't looked up the elementary plumbers manual that would have told him that anything under the well tank in the attic would have been destroyed in the fire. He decided to dig in the cellars, urged on by Dr W J Phythian-Adams, who was better on theology than plumbing. The dig took place in difficult wartime conditions on 17th August 1943. It included, according to Harry Price, Rev and Mrs Henning, 'Captain' Gregson, Dr Eric Bailey, a pathologist, his brother, and Flying Officer Creamer. Rev. Henning's gardener, Jackson, did the heavy digging. It was, indeed, fortuitous that Price had thought of inviting a pathologist along for this exploratory dig. According to Rev Henning, it was Harry Price, Jackson and himself who did the digging and it is impossible for the others to have been in the cellars too as it was piled high with rubble at the time and one had to clear a space for the dig.

...our first task was to find the' well-tank,' the sunken trough I had seen on my visit to the place in 1929. I had decided to start excavating on this site because I thought that here was the most likely spot for good results in view of Canon Phythian-Adams's analysis, the wall message ('well-tank-bottom-me'), and other indicia.

Harry Price, The End of Borley Rectory p238

However, the diggers were soon to hit a snag. He had decided that a shallow cement trough that he remembered having been in the cellar floor was the well tank. When he came to dig there, it had vanished. It had, of course been thoroughly excavated by Kerr-Pearse before the war, and he had been conscientious in replacing the concrete sink with floor-tiles matching the rest of the cellar floor

After clearing several square yards and almost boxing ourselves in with the heaps of rubble that we had piled up I was forced to the conclusion that the well-tank was missing! It certainly was not where it was in 1929.

Unfortunately, he had misunderstood Kerr-Pearse's report. The 'well tank' was missing because it been excavated and cleared six years before. Without realising the mistake, Price pressed on regardless.

It was inexplicable to me, and was just another Borley mystery. I was so certain as to the exact position of the well that I could have found my way there in the dark. Actually the cellars were not dark, as some light streamed through what had once been the hall floor. I decided to abandon the search for the well-tank for the time being, and tackle the round well, which was on the other side of the brick partition

Harry Price, The End of Borley Rectory p238

So they started by excavating the sump, discovering that it was not a well at all but a six-foot deep sump. They found some bits of pottery, the ubiquitous empty wine bottles, a broken brass preserving pan, a portion of a brass candlestick, part of a rusty iron box, sundry broken knives and a Sheffield plate cream jug (EBR, p. 239). Understandably, Harry Price had got himself very confused about the location of the wells in the cellar.

Price then determined where the well-tank had been by guesswork, and they dug at that spot. Three feet down, they came up with a bone that Rev Henning's gardener, Jackson, a former farm labourer, immediately identified as the jawbone of a pig, and passed it on to Henning, who took it on to Price. However, when it was handed to Mr Bailey, the pathologist, he pronounced it to be human. More digging produced part of a cranium. The most likely explanation is that they had dug up the remains of Kerr-Pearce's lunch as this would have all been in-fill from his dig. The 'observers' were milling about at the time and Harry Price would have had every opportunity to do a sleight of hand with the bones. The dig, after all, was a fairly chaotic affair.

As Flying officer Creamer related to Mollie Goldney 'I was wandering vaguely around the rectory grounds when I heard a commotion and on going over found some excitement over bone fragments. I was not present when Price and the others were digging, in fact I was walking around in a most casual and haphazard way unlike Price said I was in 'The End of Borley Rectory'.'

The following day, the dig was extended by several yards and yielded nothing but a couple of pendants of French origin, one of which was around eighty years old and the other one somewhat older.

Mr Jackson was 'ribbed' quite a bit by his colleagues about mistaking a human jawbone for a pigs' jawbone, but maintained all his life that what he picked out of the ground was from a pig. Johnnie Palmer, who worked at Borley Place for the Paynes, observed the dig. He saw the bones and maintained the unshakeable view that what he saw were 'awd Sows Bunz' (old sows bones). For a farmworker, mistaking pigs' bones for human bones would have been an elementary mistake. The local inhabitants were consequently incensed when Rev Henning declared that he wanted to bury the remains at in the churchyard. Bury a pig in the churchyard? The remains were hurriedly buried at Liston.

This brief dig evidently satisfied the clamour for excavation, and featured prominently in the following book, The 'End of Borley Rectory'.

The story also featured in Rev Henning's book. His account forgets to mention the presence of the pathologist and his brother, Price's secretary, and Flying Officer Creamer.

'...We had gone down into the dark cellars beneath the house to follow up a possible clue of the wall writings about a well. Mr. Price and I, with our gardener, Jackson, had first excavated the shallow well and then come round the supporting wall and dug out the narrow trough, with the result that we brought to light the portion of a skull and jawbone. …With regard to the shallow well which we, that day, did no more than empty. A former owner, when he bought the site, made it his first task to clear up the tons of rubbish lying in the cellars now open to the light of day. ... In doing this, he got down to the level of the cellar and back to the well. This he excavated and, finding the bottom was of bricks laid flat, he pulled it all down and began to dig underneath it. The well, only five feet deep, was on a solid clay bottom and there was nothing under it.'

A. C. Henning, Haunted Borley 1949

There was another attempt at digging the well in the cellar which he also recorded

'But when the owner was excavating the cellar with the help of a friend from Cambridge, with a view to finding the well before it was all closed in again, the moment they struck the edge of the wall, there was an escape of gas and much disagreeable odour which dispersed when the well was fully revealed full of mortar, bricks and fluid. This gas, percolating into the shifting and rotting rubbish may often, I think, have been the cause of a lot of the ' noises ' heard in this part of the site since the house has been demolished'

A. C. Henning, Haunted Borley 1949

After this, little more was done until 1954, when, for three years, Philip Paul, L G Rayner and Leonard Sewell excavated the cellars. Paul was a journalist who claimed that he was continuing Harry Price's work at Borley and he felt that the way ahead was to press on with the digging there. This he did between October 1954 and August 1956, attempting to find the rest of Marie Lairre's skeleton and the 'missing church plate'. He found nothing of any interest, despite the use of a large mechanical digger. Rayner and Sewell were a different matter; carefully and methodically, they completely excavated the cellars. They gave up in the autumn of 1957, after three years having found no more bones, and no church plate. Their diggings certainly proved that there was a former building on the site, as a glance at the 1773 Chapman and Andre map would have told them, but they found less in three years than Harry Price found in a day.

Any archaeologist would be suspicious of the contrast between the wonderful results of the two day dig by Henning and Price (human bones, silver jug and dateable medallions), and the completely negative results of the prior dig in the cellars by Kerr-Pearce, and the subsequent three-year dig, the exploratory dig by the BBC, and all the other exploratory work done in the 1950s. The grounds began to look like a battlefield. Yet Harry Price's brief day of archaeology had produced spectacular results. This is not the first Harry Price had had startling 'luck'. At one time he had tried to become an eminent Sussex archaeologist in emulation of his friend, 'The Wizard of Lewis' Charles Dawson, responsible for the Piltdown forgery, just thirty miles from Price's home town. Price had boasted some spectacular finds himself, including a statue of Hercules, a bone carved with mysterious hieroglyphs, gold coins from the kings of Sussex, and a silver ingot from the reign of Honorious. All have since been subject to severe doubts from professional archaeologists.

One explanation is Harry Price's remarkable luck. To compound his luck, he just happened to have had a pathologist on hand to do a positive identification of the remains, as well as a barrister to act as a witness. Another possibility was his uncanny intuition that the particular spot was the only location that would produce remains. (actually, he tried the sump first.)

It remains a possibility that the person who removed the trough planted the bones ready to be dug out. If this is the case, it is unlikely to have been Harry Price. His account of his puzzlement and confusion about the disappearance of the trough rings true. It would not have been too much of a problem to dig out the trough and replace the gap with floor tiles. Any sexton in a country churchyard will tell you that human bones are easy to come by. Price himself noted the frequency of finding human bones

'A portion of the garden of Borley Rectory is the site of the burial place of some of the victims of the Great Plague which ravaged England in 1654-5. Occasionally, a skull is turned up by the spade and other remains have been found. These gruesome relics are invariably reverently re-interred in the churchyard opposite

(Harry Price; The Most Haunted house in England p26)

Mrs Smith was said to have found a human skull wrapped in paper in the rectory, presumably awaiting reburial.

The other possible, rather painful, explanation has already been explored in the book 'The Haunting of Borley Rectory'. This is that Harry Price conjured the bones. It certainly seems odd that he was so sure that he would find bones in the cellars that he had a pathologist standing by to identify them, and a barrister to witness the dig. It is also strange that no subsequent dig found any further trace of human bones, though a few animal ones, despite digging to a depth of five feet under the cellars. However, Jackson was sure that he had dug a pig's jaw out of the clay, as was Johnnie Palmer. It would have been very obscure of Price to have planted a pigs' jawbone in the clay. It is more likely that Price was confident enough that there would be animal bones found (they did seem to be everywhere in the clay) and was primed to do the switch as he took the bone from Jackson and gave it to Mr Bailey, the waiting pathologist. This was the theory that found ready acceptance in the village. The ruse would have worked had it not been for the fact that the farm workers of the time knew a lot about their animals.

Manuscript 'Diary of occurences' by Lionel foyster quoted from FIFTEEN MONTHS IN THE MOST HAUNTED HOUSE IN ENGLAND by Vincent O'Neil

THE END OF BORLEY RECTORY by Harry Price. London: Harrap.

THE MOST HAUNTED HOUSE IN ENGLAND by Harry Price. Longmans, 1940

HAUNTED BORLEY by Rev A C Henning. (privately published 1949)

BORLEY RECTORY Glanville, S.J. (1953) Fittleworth (distributed as typescript).